|

|

||||||

"PIRATES OF PENZANCE."

I THINK it must have been during the run of Pinafore that I began to acquire that method of acting without effort which has become, so I am told, one of my most marked characteristics. I have certainly found it a very valuable asset; for if there are many people who revel in bustle, there are as many, if not more, who prefer repose. However, it nearly proved fatal to my engagement, I believe, as when The Pirates of Penzance came to be cast I was told there was no part for me. Imagine my despair. With all the sanguine enthusiasm of youth and success, I had taken an elaborate set of chambers in some mansions just off the Strand, and furnished them comfortably, though not luxuriously, and the idea of being thrown out of employment raised the vision of an immediate sale of effects, followed by a lengthy sojourn in the workhouse. However, I heard that the part of the Sergeant of Police was not yet cast, and I so worked on the feelings of the powers that were that it was eventually given to me, and it turned out one of my greatest successes. It is an abnormally short part, being only on view seventeen minutes in all. I timed it one night, but into those seventeen minutes were crowded countless opportunities of "scoring," of all of which I am proud to remember Gilbert told me I took full advantage.

We had a new prima donna for this piece — by the way, in spite of our English tendencies (to which I have already alluded), she was always called the prima donna — who was a perfect picture to look at and equally pleasant to listen to. This was Marion Hood — tall, slight, and graceful, a typical English girl with a wealth of fair hair which, I believe, was all her own. Her singing of the waltz song, "Poor Wandering One," was quite one of the features of the first act, especially on account of what Sullivan himself called "the farmyard effects." I only appeared in the second act, and my song, "The Enterprising Burglar," was such an immense success that I had always to repeat the last verse at least twice. It occurred to me that an encore verse would be very nice, and in a rash moment I one day presumed to ask Gilbert to give me one. He informed me that "encore" meant "sing it again." I never made such a request again, but I heard it whispered that years later, in a revival of the opera, the comedian playing the part was allowed to sing the last verse in three languages as an encore. The first performance of Pirates very nearly had to be postponed on account of an accident to Miss Everard, who was to have played the part of Ruth; she was delightful as Little Buttercup in Pinafore. She was standing in the centre of the stage at rehearsal one morning, when I noticed the front piece of a stack of scenery falling forward. I called to her to run, and got my back against the falling wing and broke its force to a great extent, but it nevertheless caught her on the head, taking off a square of hair as neatly as if done with a razor. The shock and injury combined laid her up for some time, and there was consternation in view of a postponement. Fortunately I was able to suggest to Carte a clever and dear old friend of mine, by name Emily Cross, who I felt sure would be capable of replacing Miss Everard in the time. She was telegraphed for, and after much pressure she consented, and with only two days' study and rehearsal appeared and made a great success. She once told me a rather good little story against herself, of the days when she was a Shakespearean star-actress, and at the time playing Ariel at the Theatre Royal, Newcastle-on-Tyne, where she was a tremendous favourite. She was crossing Grey Street on a very wet and muddy morning, and being a careful woman raised her skirts well out of possible contact with the mud. Having crossed safely, she proceeded to lower them to the orthodox length, when a small street urchin remarked loudly, "Yow needn't be so particular about 'em, Emily ; we can see 'em all any night for tuppence."

The run of the Pirates marked two important crises in my life. I had always been a very keen footballer, and at this time was playing for the Crystal Palace club, which, at its full strength, numbered some very good exponents of the game; indeed, when county football was inaugurated and the first match was played at the Oval between Surrey and Middlesex, I was one of five players on the one side fighting three on the other, all out of our first team — a pretty good average for one club. What jolly matches we had too all round London, even going as far as Chatham to play the Sappers (a long journey in those days), who then had Vidal and Marindin playing for them.

Forest School was one of our most enjoyable fixtures, and the scene of one of the crises I have alluded to, and also my last match. On arrival I found that I had not brought my barred boots with me; but, nothing daunted, I played in my walking boots, with the result that I came down heavily in turning, my right knee going out and in with two cracks like the report of a pistol. Of course, I "retired hurt," but after a spell of rest went, rather foolishly, to work again, with the same result. I got back to town in great pain, but went to the theatre as usual; but when I had been knocked down by the Pirate King and should have risen in my turn and felled him, I had to ask him to help me up. He kindly did so, and I went to bed for three weeks. No more football after that!

The other crisis was less exciting but equally mortifying in a way. Up to this time I had frequently been both honoured and flattered by receiving letters from anonymous correspondents breathing admiration and, in some instances, ardent passion. Some of them were, I know, genuine; how I know it this is neither the time nor place to explain, I may write a novel one of these days; but with the production of Pirates they ceased entirely. I incline to the belief that my appearance as the Policeman was regarded as being my true presentment, and they were therefore disillusioned. This point of view has subsequently been traversed by a cheerful doubt, induced by an intermittent recurrence of those charming attentions, up to within some ten years ago, when the force of circumstances compelled me in several plays to undertake the roles of much-married foreign potentates, since which they have entirely ceased. Apropos this actor-worship, I was once at a ball where a lady to whom I had just been presented said, "Oh, Mr. Barrington, my daughter has fallen madly in love with you. May I introduce you? "I murmured an embarrassed "Certainly," and she turned to a very pretty girl who was standing near, saying, "Marjorie, this is Mr. Rutland Barrington." The girl's face lit up with excitement and pleasure; she took a good look at me, and turned away with a long and disappointed "Oh!" That mother knew something.

About this time the cult of æstheticism was invented, and it had some weird results, though it took such a firm hold on some people that to this day we see strong evidences of its transmission from mother to daughter, the highly aesthetic young man being fortunately about as extinct as the dodo.

To such a man as Gilbert the chance of shooting folly as it flew naturally proved irresistible, and the result was the writing of Patience, quite one of the most delightful operas of the series, which was produced at the Opera Comique in 1880 (sic.). My part of the Idyllic Poet was originally christened Algernon Grosvenor, but was eventually changed to Archibald at the request of the rightful bearer of the original name, though I could never understand why such a notoriously athletic man and golfer as he was should have been nervous of unfavourable comparison.

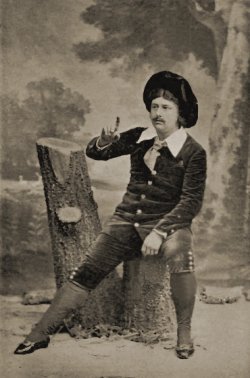

Patience was a great success from the commencement, and Carte who had earlier begun to realize that a larger, more beautiful, and permanent home would be wanted for what appeared to be a class of entertainment that had come to stay, expedited the building of the Savoy Theatre with the intention of migrating there with our latest success. It was indeed an exciting evening in our lives when the move was made, and the welcome given to us in our new home was something to remember. At this lapse of time I am not quite certain whether there was a break in the performance or not, but I rather think we played one night at the Opera Comique and the next at the Savoy. I had another strong reason for remembering this first night, for I was almost voiceless. I had implored both Carte and Sullivan to excuse me from playing (my dialogue I could speak, so had no occasion to trouble Gilbert), but they declared they would rather have me with no voice than alter the cast on such an occasion. I was glad afterwards that they had been firm about it. After the Opera Comique both the stage and auditorium of our new home seemed enormous. There was one very excellent arrangement for the convenience of the artists in crossing from one side of the stage to the other (which was impossible at the Opera Comique without going underneath the stage) in the shape of a kind recess at the extreme back of the stage, with an arched passage on either side. We were all pleased with this, but the scenic artist had noticed it and when the curtain rose on the first night we found the recess in use for the set and ropes put up to prevent any one crossing in sight of the audience and we never had the use of that passage, but went under as before. Still, it was very sweet of the architect to design it specially for us. The passage and the arches have now totally vanished, under the order of the L.C.C. In addition to my voice trouble on the first night, I had another awful contretemps to contend with. When I took my seal on a rustic tree-trunk preparatory to singing "The Magnet and Churn," I heard an ominous kind of" r-r-r-i-p-p-p!" and immediately felt conscious of horrible draught on my right leg. I knew, of course, what had happened ; my beautiful velvet knee breeches had gone crack. It was an awful moment, as I could not possibly ascertain the extent of the damage, and had a song to sing and a scene to play before I could leave the stage. Had they but been made of red velvet it would not have mattered so much, for I felt I was blushing all over and it might have escaped notice, though some of the aesthetic maidens were already choking with laughter. What I did was, to shuffle all through the scene, and shuffle off sideways as soon as I could; but no one who has not suffered a similar experience can guess at the agony of mind I went through.

My old friend Arthur Law, who was then a budding author, was another recruit to our ranks during this piece, being engaged to understudy me as Archibald Grosvenor. Before finally committing himself to the engagement, he paid me the compliment of asking my advice on the contract he was expected to sign. It was certainly one of the most comprehensive documents I ever read, as after the usual clauses to the effect that he was to "understudy, play old men, women, or juveniles, and anything he might be cast for," it ended with this highly humorous clause, " and write first pieces when required "; and all this on a weekly salary, and "weekly" might well have been spelt with an "a."

In 1882 Patience was followed by lolanthe, which, by the way, was originally christened Perola, a kind of superstition having arisen in favour of titles beginning with a "P," and why it was changed I do not remember, but certainly lolanthe is the prettier. It was in this play that one of the less important but beautiful fairies captivated the attention of certain young peer who afterwards proved fickle, at considerable cost to himself. He mystified me very much one night when visiting my dressing-room before I was aware of the attachment which made him such a frequent caller on Grossmith or myself by saying, on my remarking that he would shortly know the piece by heart, " Well, is not she worth it?" It puzzled me for days in fact, until the engagement was announced.

Durward Lely and I had a scene to play, as Tolloller and Mount Ararat (sic), which, at rehearsal, appealed to both of us as so intensely funny that we absolutely could not get on with it for laughing, this occurring for several days running, until we were almost hysterical over it. Gilbert said he only hoped the audience would laugh half as much as we did, but on the first night they did not. I believe we both funked it, and consequently did not play it well, because it was afterwards quite one of the best scenes in the piece; but our blank looks on the first performance must have been funny.

One night Richard Temple, who was playing Strephon, failed to appear at one of his entrances, when he should have rushed on singing "'Tis I, young Strephon." We waited for what seemed like half an hour, amid the noise of scuffling feet and shouts of "Temple! Mr. Temple!" in the wings, but there was no sign of him. I then sauntered off the stage, endeavouring to give the impression that I was going nowhere in particular, and the moment I was out of sight rushed to the green-room, where I found him half asleep over a newspaper. I dragged him to the stage, gave him his note, and (being an old hand at the game) he went on quite calmly and picked up his cue, and behold! he was one-sixteenth sharp. It was a score for me.

lolanthe was the medium of Rosina Brandram's first great success. Jessie Bond was ill, and she was the understudy, and I well remember how she electrified the house with her glorious singing of the song in the second act where she appeals to the Lord Chancellor for her son. I have never heard a contralto singer who gave me so much pleasure as Rosina; she sang without any effort, and her voice had a fullness and mellifluous quality which were unrivalled. She did not shine as an actress, and I frequently expressed my surprise that she did not turn her attention to Oratorio; she always said she would like to, but I think the glamour of the stage life was too strong for her.

lolanthe also furnished the debut of Manners, who was the original sentry and scored a great success with his song. This is yet another instance of the success of a part not being influenced by its length, as it is, if anything, shorter than the Sergeant of Police in Pirates, but presented equal opportunities of scoring. I wonder whether in all the parts he now plays, or has played with the Moody Manners Opera Company he has found one which brought as much kudos with a little effort.

Alice Barnett, the original Fairy Queen, had a voice which was almost as massive as herself, and I remember how pleased she was with the shout of laughter which greeted her allusion to Captain Shaw in her apostrophe to Love. All the heads in the house turned to the stall which was occupied by the gallant fireman, the mention of whose name called forth a round of applause. There was some- thing almost pathetic in the recollection to many of those present in 1907 at the revival of the opera, for although the veteran was present, time and illness had robbed him to a great extent of the old erect and gallant bearing.

Here is a quaint little series of coincidences connection with lolanthe. I was writing a part of this chapter, dealing with the piece, while on a visit to Worthing, where I was giving a recital, and on finishing my morning's work went to pay a call on the local entrepreneur, who also edits and runs the local newspaper. He had just got out his "contents" bill, and the headline was " lolanthe"; it referred to a school performance in the neighbourhood. While we were chatting the town band took up a position opposite us, and, of all things started playing an lolanthe selection, beginning with my song. To complete the humour of the situation when I turned to my friend and asked him what the air was, he failed to recognize it.

Somewhere about this time a "curtain-raiser" called The Carp was produced, in which I, as an angler, was much interested. The angler was played by Eric Lewis, who had lately taken to the stage after a preliminary canter over the entertainment course, much the same as Grossmith and myself. At the end of the play each night he caught the fish, and was very triumphant over it; and being a pretty little piece, and clever, it ran for a long time — in fact, so long, that one night on the capture of the carp, a voice from the gallery came, in answer to Eric Lewis's joyful "I've caught it!" with, "About time, too; it's high by now!"

Page modified 29 August 2011