|

|

||||||

ABOUT this time Sullivan began, I think, to tire ever so little of his continuous devotion to comic opera, and to sigh for a larger field of battle. He must also have affected Carte with the same idea, for while he began to compose the music for Ivanhoe, for which Sturgess (sic) provided the libretto, Carte began to build what was intended to be a permanent home for English Grand Opera, the result being one of London's most beautiful theatres, which is now known as The Palace Music Hall in Shaftesbury Avenue. How magnificently Ivanhoe was staged and played! There was a double company for the opera, as it seems to be a tradition that Grand Opera artists cannot possibly sing every night in the week. I presume they are a more delicate race than the hardy Comic Opera people.

Although Ivanhoe itself was a great success, the venture was found impossible to work at anything less than a heavy loss, and it ended with the final dreadful transformation of the theatre into a music hall.

I do not intend by this the slightest sneer at the "Halls," in some of which, notably the Coliseum, I have been welcomed and made to feel happy; but it did seem sad that this great attempt to found a home for English Opera, on the part of a successful manager and the greatest composer England has ever known, should meet with such a poor recompense. And yet in the face of this failure there are periodical outcries for a National Theatre, which is not really desired.

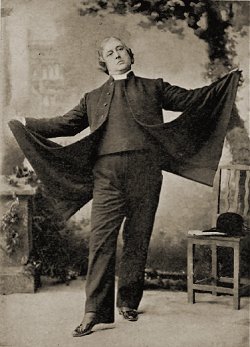

In the meantime we had at the Savoy a fresh combination of talent in the persons of Sydney Grundy and Edward Solomon, who were responsible for The Vicar of Bray. This opera, though lacking many of the most striking features of our former pieces, was a marvellous success, considering the standard that had been set up, and personally I simply revelled in the part of the Vicar — an extremely hard-working one, by the way, it being the nearest approach to a "one-part piece" I have ever played in. So patent was this that one of the stage hands said to me one night, " Well, guv'nor, blest if you ain't earnin' all our money for us in this bloomin' piece!" only he said neither "blest" nor "bloomin'."

By way of a kind of holiday, combined with business, I went on a short tour with The Vicar in the Isle of Wight, and as it was my first visit there very much enjoyed it, although some of the places we played in were rather cramped, being for the most part town halls. In Shanklin one night, just as I commenced my first song, a donkey outside appeared to think he had also received his music cue, and as he was evidently the Lablache of his company the duel was manifestly unfair, and I eventually had to resign. I came forward and told the audience that I would continue my song as soon as my parishioner had finished. That put them in good humour; we waited a little in silence; the donkey finished with a cadenza in D major, and all was well. I was rather nervous of further interruptions, but he left the neighbourhood at the end of the first act, having, I think, discovered that in Act II I did a dance that he knew would be too much for him.

We had an awful experience on this tour in going from Jersey to Weymouth, where we were due to play about three hours after arrival. It was a terribly rough passage, the boat fairly standing on the rudder most of the time, and nearly every one was very ill. I was one of the lucky ones, but I nearly managed it when I went to the saloon for some dinner. We arrived safe and sound at Weymouth, but three hours late, so had to go direct to the theatre and begin. I do not know who was the architect of that theatre, but he could not have allowed for any foundations, for the whole place was going up and down like a ship at sea, and when it came to dancing I could not tell which foot was off the floor and which on, until I finally found that both were off, so sat down to reason it out. However, we worried through, and I was glad to seek the shelter of my hotel; but on the way there I met an old friend who was spending his holiday in Weymouth, and he was most enthusiastic about the fishing. Would I go with him? Certainly I would, but not then. "No; but will you come to-morrow?" I said I would think it over, as I had had nearly much sea as I wanted. "Well," said he, "I shall call for you when I start." "All right," I answered; "at what time?" "About four," said he. "Very well," I replied, "but don't be vexed if I'm out." "Out, my dear fellow! You must have some sleep!" The lunatic meant four in the morning! I left hurriedly, and am glad to say I have never seen him since.

We returned to town in June, 1891, to give yet another author his chance at the Savoy, in the person of Mr. George Dance, whose Nautch Girl was, I believe, his maiden effort (no joke intended and none taken), and to this opera also Solomon set the music, and very charming indeed it was.

"NAUTCH GIRL."

Solomon was one of my most loyal admirers, and I was much amused when he came to me one day in a great state of indignation because Dance had suggested that possibly the part of the Rajah of Chutneypore might be beyond my capabilities. The little man was honestly wroth at what he considered a slur on my reputation; but as he is dead and Dance is alive, I will not quote his actual words on the subject. Anyhow, I played the part and the composer was delighted; whether the author was or was not I never heard, but in any case I won half the battle.

During the two foregoing London seasons I had been playing some original musical duologues to which my prolific friend Solomon had also supplied the music, in company with my little comrade Jessie Bond, who was gifted with a personality which made her a universal favourite, and we had formed an impression that a provincial tour would be both amusing and profitable.

I accordingly arranged one with Vert, the well-known agent, for that autumn, we being very kindly released by Carte for three months on the distinct understanding that we then resumed our parts.

The little tour was a great artistic success, which gratified me the more as I had written all the little pieces myself, but we came to the conclusion that the provinces were no gold mine, and the first trip was also the last. One of our worst houses was at Barnard Castle, where the intelligent local agent had recommended the day of the annual flower show and fireworks. There were only three reserved seats taken, so I hastily requisitioned the services of the town crier, who went all round the place announcing that the entertainment was postponed, and we attended the fireworks ourselves. This was the only occasion on the tour when we turned away money.

During my absence from the Savoy my part of the Rajah was taken over by Penley, as great a physical contrast to me as could well be imagined, not to mention the difference in method. He told me that he did not feel very happy in the part, and I found it easy to believe on hearing that on one evening some rude person in the gallery interrupted him in the middle of a speech and inquired loudly, "Where's Barrington?" Penley turned to one of his comrades on the stage and remarked plaintively, "I'm having a rosy time of it, ain't I?" I should rather expect something of the same sort to happen if I were to make my appearance as Charley's Aunt, which I do not mean to do.

Courtice Pounds had a very good part in this piece, which he invested with the charm he brings to all his work, and I used never to tire of listening to his solo when in prison, followed by a very catchy duet with Jessie Bond, their voices blending particularly well. Pounds was also very popular as the smug curate in The Vicar of Bray. He used to say that when playing in The Gondoliers, in which his part and mine were so closely associated as to be a kind of duet, he felt he must develop a stronger vein of comedy, to keep level, as it were, and there is no doubt that he did improve in his acting enormously from that time, and I think put the seal on his fame by his delightful rendering of the Clown in Twelfth Night with Tree some few years ago.

The latter end of this year saw me back at the Savoy, where I once more took up my part of the Rajah, and we also began the rehearsals for Haddon Hall.

Still another combination of author and composer was tried in this piece, in the hopes of wooing a return of some of our former glory. I believe it to have been Sydney Grundy's first flight into the realms of opera, and he could hardly have chosen a more attractive theme or one more likely to appeal to Arthur Sullivan.

Grundy has always appealed to me as the typical John Bull kind of man, and when he told me he was going to spend a fortnight or so with Sullivan in the south of France in order to arrange the sequence of musical numbers and other matters, I could not refrain from expressing my surprise and anxiety as to his diet. He had evidently had the same fear himself, for he answered at once, "Sullivan guarantees English cookery"; but all the same, he confessed on his return that he would infinitely rather have spent the same time with Sullivan in London. There was, of course, some very beautiful music in Haddon Hall, and Rosina Brandram's song, " Queen of the Garden" and the duet "Friendship," in which she was joined by Richard Green, were two gems. I always felt that my part in this play was a kind of excrescence, being in fact written because I was there, and possibly wanted there; but it should really have been the villain of the plot, and a serious rival to Courtice Pounds in the love interest, instead of a would-be humorous combination of the two.

Haddon Hall had not been running long when the welcome news flew round the Press that we were to once more find our Utopia with the two original magicians, who were engaged on a work bearing that title, and sure enough we were duly summoned to a reading.

This was fixed for a Monday, and I had been spending my week-end at Ryde, and to my intense annoyance the boat-train was late and threatened to make me unpunctual. I sent a long explanatory telegram from Mitcham Junction begging them not to wait, but found to my chagrin, on arriving about half an hour behind time, that Gilbert had most kindly insisted on waiting for me. Both Sullivan and Carte abused me heartily for "daring" to be late and keep Gilbert waiting, and seemed to think I ought either to have got out and run or never gone away at all. It was rather amusing, as after all the call was the author's special call, and he was quite charming about it.

We had a fresh importation for this opera in the person of Miss Mclntosh, who played the principal soprano, and imported a great amount of delicacy and refinement to the rôle of the Princess Zara, qualities which gave additional point to the Utopian dreams it was her duty in the part to voice.

Although a success, it did not achieve one of old-fashioned Savoy runs, and I rather incline to think that this may have been in some measure due to the second act, which was not as full of fun as usual; indeed, a great part of it was taken up with the realization of a "drawing-room " with the presentations made in due form, and perhaps it may have been a trifle tedious. It was great fun for the company on the days when we had a lady professor of deportment attending rehearsals to teach us how to bow. I believe there was also a certain amount of friction in a very high quarter over the fact that when dressed as a field-marshal and wearing an order confined to a very select few, I took part in a species of nigger-minstrel number which was rounded off with a breakdown. There was a very bright young baritone named Scott Fishe, who had the part of a financier and sang a song about "The English Girl," which in my humble opinion was one of Gilbert's best efforts. Denny, John le Hay, and myself, also had a very excellent dancing trio in the second act, and le Hay was quite admirable all through the play; indeed, the more I think about it the less I understand why it did not run longer.

Utopia was, after all, not to prove the recommencement of a series, and Gilbert and Sullivan drifted apart once more at the end of it, and again we had to fall back on extraneous talent. This time Carte appeared to desire something quite out of the beaten track, and the result was a very weird piece indeed written by J. M. Barrie and Conan Doyle, to which Ernest Ford supplied some very excellent music. I have never to this day been able to discover with certitude what it was all about, and the title Jane Annie can hardly be described as illuminating, at least to the average mind, whatever it may be to the thinker.

The second act was full of allusions to golf, and the scene was actually laid on a golf green, and the whole thing seemed to puzzle our audiences very much, golf not being in those days the well-known factor in life which it now is. The best part in the piece was a caddie, and only one or two of us knew what a caddie was. I myself played a Proctor, and, for some reason which I have forgotten, hid myself in a clock, a most uncomfortable position always, and especially so one night when I sneezed violently and my spectacles, which formed the hands, fell off.

The whole Savoy company went out on tour with this opera, and I am bound to say that they seemed to know more about it in the provinces.

Ernest Ford went with us as musical director, and he, Scott Fishe, Kenningham, and myself generally stayed in the same house, being all four keen golfers and I remember being much amused at our landlady in Birmingham, who stared in amazement at our bags of clubs on arrival, and exclaimed, "Bless my soul! what are them fakemajerkers?" It struck me as such a lovely word that I have never forgotten it. After we had been three days in her house, and I had collected my golfers each morning about nine and gone off for the day, she said to me, "Well, I've never seen such a queer lot of actors." I asked her what complaint she wished to make, when she replied, "Complaint! I likes yer. All the actor folk who comes to me lies in bed till two o'clock in the day! You're no trouble at all — it's a 'oliday for me." And nothing was too good for us for the whole of that week.

We had an extraordinary and almost incredible experience in Bradford one night with Scott Fishe. He and Kenningham had deserted golf for one day to take part in a cricket match against a team that I described with would-be humour as Licentious Victuallers, and when Ford and I returned from golf we found each of them fast asleep on sofas in the sitting- room. So far so good; but it shortly became time to go to the theatre, and though we eventually aroused Kenningham, nothing we could do would waken Scott Fishe. He could not be left — time was flying — so between us we half carried, half pushed him round the corner, got him dressed, and stood by him till his cue came to go on the stage, and literally shoved him on. He went through the dialogue of his scene, sang his song without making the slightest mistake, came off the stage and woke up! not having a notion what he had done.

Page modified 29 August 2011