|

|

||||||

![]()

THE subject of "encores" in connection with the question of "to be or not to be" has always held a great fascination for me, and I have frequently thought that it might prove amusing, and perhaps illuminating, if a plebiscite could be taken of the wishes, for and against, of theatre and concert goers.

With the subject constantly fermenting, as it were, in my brain it came to me as an agreeable surprise that I should be asked to read a paper on the matter to the members of the O. P. Club in January 1909, and it was with no little gratification that I seized upon the chance of airing my own views on a much-discussed question.

Having a very keen sense of the position held by the members of this old - established and popular circle in relation to music and the drama, I felt it incumbent that I should not go into battle without some survey of the ground, and with that object in view I devoted myself, for a few weeks previous to the occasion, to obtaining some idea of the attitude of the general public towards encores, by means of questioning all and sundry whom I met possessed of the necessary time, inclination and patience to afford me replies.

The answers I received, had they been rendered in the form of a "show of hands," would have been fairly level, but many of the added remarks were extremely interesting, amongst which was one which impressed me as being a view of the situation which presented itself to few. It was made by a lady, who objected to encores on the ground that they must be an unfair tax on the artist. This opinion I believe to be shared by the profession at large, although I fancy that the most hardened cynic would admit that it is a tax which is greeted with a resignation indicating great nobility of character, scarcely exceeding that with which certain other descriptions of taxes are met.

It is perfectly obvious that we have, at least partially, reconstructed the meaning of "encore," in the case of singers we most certainly have, for whereas it formerly meant "sing it again," the modern definition of the compliment is usually "sing something else," and, with a special reservation in the case of some songs, "the same tune if you like, but other words." This perversion of an antique meaning may perhaps have come about through the prolific tendencies of modern lyricists, who have more to say than they can possibly put into two or three verses, and wish their hearers to suppose that the verses increase in interest in the same ratio as they do in number. This explanation has forced itself on my attention on many occasions when, as a member of the audience, I have found the demand for an encore so insistent as to leave the public no option in the matter.

There is little doubt that many artists, while detesting encores, at the same time feel a keen sense of disappointment if they are not forthcoming; this apparent paradox may in many cases be explained by the fact that so many managers measure the success of a song or number by its encore-securing qualities, this test of discrimination has even, within my experience, led to the suppression or elimination of items of a tender or emotional character which could only be received with an appreciative silence which is sometimes accompanied by that little sigh of pleasure which is infinitely more grateful to the true artist than would be a noisy demonstration of approval.

We do not less enjoy, or are less impressed by, the Hallelujah Chorus because of the customary silence which ensues, though this is perhaps hardly a fair example to quote, all oratorios being received in the same manner.

That a genuine encore is a genuine compliment I presume few would question, but to determine the proportion of credit due to the earner of the reward is a somewhat difficult proposition. The author of the lyric, the composer and the artist who renders the song have each a claim, and possibly the last-named of the triumvirate could offer an immediate solution, but it does not follow that it must perforce be the correct one.

Equally obvious is the fact that a genuine encore has all the effect of a powerful stimulant to the artist, and, happily, none of the resultant depression of an overdose of the real article, and, if for this reason alone, is a very desirable thing, from the point of view of the public, as an incitement to further flights of energy, for their behoof, on the part of the recipient.

There are those who maintain that without encores the public would not consider that it had received its money's worth, but this, on the face of it, is bad reasoning; the audience pays to hear a play once on an evening, and with the ever-present British sense of justice would never dream of demanding more than it was entitled to: to my mind a certain indication that the encore is one of the many charming and spontaneous expressions of pleasure and good will which it delights in showering on its favourites.

I have often heard the question raised: Who is the proper person to accept an encore? – and here again I find great diversity of opinion. In my own humble opinion the responsibility rests, in the case of a solo, entirely with the artist concerned, and, in the case of a concerted number, with the musical director. This opinion was stoutly combated by the director of one theatre in which I was engaged, who claimed the right of decision in all cases, and who, I believe, was scarcely convinced that he was in error even after I had pointed out the fact that it was in the power of the artist, on an encore being accepted on his or her behalf, to which for some reason he or she felt a disinclination to accede, to make a quiet exit and leave the musical director to find a way out of the impasse! I am pleased to record the fact that the matter was never put to the test by myself in the manner suggested, which I also accept as a tacit admission of the correctness of my view of the solo side of the question.

When we take into consideration the fact that a successful play involves the giving of at least one matinée per week, at which, in spite of a rather widespread belief to the contrary, the majority of artists concerned are conscientious enough to "put in all they know," as much as at an evening performance, it becomes obvious that the strain is doubled, and does indeed become something of a tax on human resources, to such an extent, in some cases, as to lead to a song being "cut," which is perhaps the reason of the aforesaid belief, but the cavillers do not always reflect that they would sooner have the artist minus a song, than the play minus the artist.

Among the remarks made to me on the subject, by sundry friends whose opinions I requested, was the very pertinent one, a side issue possibly, now frequently expressed: "Why is the orchestra allowed to be so overwhelming?" This led to the opening of a new field of questions on my part, during which I arrived at the conclusion that audience and artists alike share the grievance of the strenuousness of many of the modern orchestral accompaniments, in some cases amounting to a battle, in which the overwhelming odds must end in a defeat of the artist.

The orchestra is afforded its opportunity in overture and entr'actes, and, in accordance with the opinion of artist and audience alike, should, for the remainder of the time, act as a lifebuoy of support to the singers, and not a foaming wave of melody beneath whose resistless force they must inevitably drown.

I do not for a moment wish it thought that, in writing on this matter, I am accusing any particular musical director, my own theory being that, with few exceptions, they are all addicted to the possibly natural idea that their musicians' contribution to the entertainment is the paramount consideration, and if honestly convinced of this they are but laudably fulfilling their contract – but other people may hold different views, and be equally convinced of their correctness without the opportunity of expressing them.

The musical director is the master of the situation, and in him alone is vested the power to decide whether the artist or the orchestra shall be most in evidence; that it most certainly does not rest with the members of the orchestra themselves was made perfectly clear to me when conversing on the subject with some of my orchestral friends, who informed me that, owing to the propinquity of other instruments, they can only be aware of the strength of tone they are giving by a signal from the director to increase or modify it.

I am bound to admit that, of late, I have noticed at several theatres a greater consideration than obtained formerly in this respect, resulting in a marked increase, at all events in my own case, of the pleasure with which audiences listen to musical plays.

When I ventured on embodying some of these remarks in the paper to which I alluded at the commencement of this chapter, I was intent on airing a grievance which, I had satisfied myself, was shared by countless patrons of the theatre, not to mention countless artists, and which I hoped might be ventilated without rancour, but the remarks then aroused something in the nature of a storm in a teacup – one journal describing the incident as "an attack on the orchestra," which it most certainly was not, nor was it intended to be, it was simply a plea for the modification of the prominence given to one feature of what is undoubtedly intended to be a harmonious whole, and if I have in any way been instrumental in wounding the feelings, in ever so slight a degree, of my friends the instrumentalists, I here and now beg of them to forgive me as freely I forgive them, which should be an easy task, as I have never succeeded in partially drowning the orchestra, in spite of many gallant efforts in the piano passages.

Another journalist immediately "interviewed" my old friend François Cellier on the subject, jumping to an erroneous conclusion that my remarks were levelled at him, and while making merry, in a mild way, at my expense he, very naturally and properly, disclaimed the slightest possibility of blame attaching to himself or his famous Savoy orchestra, but he might not perhaps have been quite so satisfied on the point had he overheard a remark made to me a day or two later by another "late" Savoyard (and a really eminent singer) to this effect – "Oh, Barry – how I have suffered sometimes from the loudness of the accompaniments!"

The best of us are not infallible, but I do not think we have an English conductor with so distorted a view of his duties as a certain well-known German director who was rehearsing his play, and at one point shouted from the stalls: "Lauter! lauter! – I can still hear a voice!"

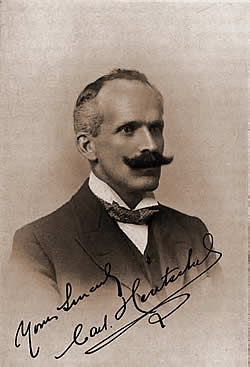

Whatever the general opinion may be on the subject treated in this chapter I certainly appeared to have the sympathy of the members of the O.P. Club on the evening in question, with the exception, perhaps, of one speaker, in the short debate which followed, and who was good enough to say that, although I had interested and amused him, he did not consider that I had thrown a particularly illuminating light on the matter, a blow to my feeling of self-satisfaction which was softened by the humorous twinkle in his eye and fully restored by the hospitality of my host and old friend, Carl Hentschel, the president of the club, as exhibited in the East Room.

I must confess that since then I have not noticed any appreciable falling off in the encores I secure, nor have I been overwhelmed with evidence of an orchestral desire to profit by a well-intentioned hint.

Page modified 2 February 2008