|

|

||||||

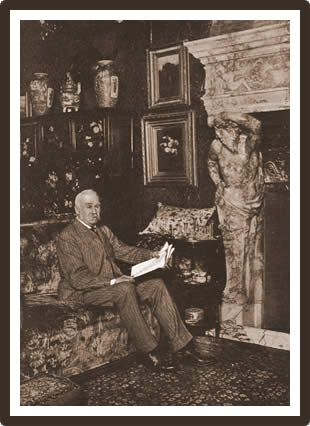

Mr. W.S. Gilbert at Grim’s Dyke

by Wentworth Huyshe

|

Taken at a special sitting by the "Graphic" photographer |

"We have met before, have we not?" said Mr. W.S. Gilbert as he advanced to greet me on entering the study of his beautiful house in the Weald of Harrow. I reminded him that it was in 1882, at the dress rehearsal of Iolanthe at the Savoy Theatre that we had met, and we talked awhile of that and of the notable frst night, which followed it and began a run of thirteen months — that quaint conceit which presented us with a fairy Grenadier Guardsman and a fairy Lord Chancellor, and the charming strains of "O, Foolish Fay," with its allusion to the love-quelling cascades of Captain Shaw’s Fire Brigade.

"And now we are set to have a revival under your own direction, Mr. Gilbert, of Iolanthe, I hope, and the others of the great series which captivated England in the seventies and eighties, and in the familiar house identified with them."

"That is Mrs. Carte’s intention," said Mr. Gilbert.

"And you will begin with The Yeomen of the Guard, rehearsed under your own direction?"

"Yes; I shall stage manage that and the others — in the interests of the pieces themselves."

This was a remark which seemed to me somewhat perplexing, and to require elucidation. I was helped out of my difficulty by the perfectly frank and kind courtesy with which my inquiry was met. And here I may say that if there are any who have been misled by vague diatribes against Mr. Gilbert, to the effect that he is an ill-natured man and so forth, that notion would be at once dispelled upon a personal acquaintance with him. As he himself says, he has never had an angry word with any member of the Savoy company during the twenty years that the stage was under his personal control. He attributes the idea to his having been blessed with a constitutional frown, which is a purely physical fact, and gives no clue to his real nature.

"In the interests of the pieces themselves, Mr. Gilbert? But the pieces are as right as ever they were, are they not?"

"Well, I hope so; but in a few years they will revert to me, and I do not want them to come back with diminished reputation."

"But…"

"I’ll tell you what I mean. Mrs. D’Oyly Carte and I have been on the friendliest terms for these twenty-five years and more. She is a lady for whom I have always entertained a profound regard, and who has hitherto invariably treated me with perfect kindliness and consideration. In the old days of the Savoy productions the arrangements between Sir Arthur Sullivan and myself and Mr. D’Oyly Carte were on a basis which was mutually satisfactory to all three of us. Sir Arthur and I were absolute autocrats behind the curtain, and Mr. D’Oyly Carte equally absolute in front of it. To me fell the histrionic training of the performers in my pieces, and Sir Arthur Sullivan and I decided the cast. The music was, of course, under Sullivan’s direction, and the stage management was entirely controlled by me. Mr. Carte had complete control of the auditorium. For instance, when he reduced the price of boxes from three to two guineas without consulting us we said nothing; it was not in our department, and was a matter entirely under the control of Carte. So, you see, the triple alliance worked quite well."

"Why, yes, it was a thing that all of us who lived in the Savoy golden age right through the eighties thought would be broken only by death."

"Well, it was broken for causes into which I need not enter, but which had nothing whatever to do with the actual work of production. Nothing, as I have said, occurred to disturb the friendly relations between us and Mrs. D’Oyly Carte, both before and after she became Mrs. D’Oyly Carte, and, of course, she was as familiar with our arrangements and the divisions of our responsibilities as we were ourselves. Well, Mrs. Carte is about to produce The Yeomen of the Guard at the Savoy, and although I am to stage manage it, I do not know the name of a single individual who is to play in it. In casting the piece as she pleases, Mrs. Carte is entirely within her rights, as, in making my contract with her, it never occurred to me to stipulate for a privilege which has been accorded to me, as a matter of course, by every manager I have had to do with for forty years past. And now that is really all I have to say that would be of interest to you or the public. Would you like to have a look round the place?"

And so we went on a little tour round the beautiful mansion and grounds of the master of Grim’s Dyke, and along the woody banks of the Dyke itself, the ancient boundary of the Kingdom of Casivellaunus, whose capital was at Verulamium (St. Albans)

"It is only about a mile from here," said Mr. Gilbert, as we were talking archaeologically of Grim’s Dyke, "that Boadicea killed herself to escape the attentions of the Roman General — so the old story goes."

It is a fascinating feature of Mr. Gilbert’s estate, this strange mere-like, ancient dyke, with its still brown water and its wooded banks — a weird thing, and made still more weird by the forlorn statue of Charles II. — the very statue which originally stood in King Square (now Soho Square) when it was first built and named after the Merry Monarch — which stands in the Dyke itself. I wanted to suggest to Mr. Gilbert that the Guildhall Museum would be a more fitting place for this interesting relic of Stuart London, but I merely reflected a moment upon the strange fate of certain fragments of old London — Temple Bar in a Hertfordshire park, and Charles II. in Grim’s Dyke!

Very interesting are some of the "properties" to be seen here and there among the costly and beautiful objects with which Mr. Gilbert’s house is filled. In the entrance hall is a grand model, 14ft. long and 16ft. high, of the three-decker line of battle ship Queen, 100 guns, one of the last of the wooden walls of England. This immediately suggests H.M.S. Pinafore, that famous craft whose captain, on being pressed, qualified his statement that he "never was sick at sea" by substituting the phrase "hardly ever," which became one of the popular sayings of London during and after the run of that famous early Gilbert and Sullivan work. This model, indeed, is not only a model of the old battleship, but part of it seved as model for the stage quarter-deck of the Pinafore, of which Lord Charles Beresford remarked, at the dress rehearsal, that he could not find a single fault. Mr. Gilbert said that he found great difficulty in getting the model kept in good order nowadays, for there were few who are able to rig an old-fashioned three-masted battleship. The old salt who used to set her running rigging to rights when it got slack is now dead. In the billiard room are the terribly realistic block and axe which were used in the Yeomen of the Guard during its original run at the Savoy. They were exactly copied, by special permission of the Constable, from the actual examples preserved in the Tower which were used for the execution of Lords Kilmarnock and Balmerino.

"And are they to be used again when the Yeomen of the Guard is produced in the revival, Mr. Gilbert?"

"I don’t know. I have not been asked for them."

In the billiard-room also there are large frames containing photographs of the characters in the original casts of the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, and between them are hundreds of the original drawings made by Mr. Gilbert himself for the immortal Bab Ballads. In this room are thus gathered pictorial reminiscences of Mr. Gilbert’s literary and dramatic career, from the days when his quaint and original genius first burst upon an astonished and delighted public thirty-five years ago. Close by, on the adjoining landing, is a thirty years ago photograph of Mr. Gilbert in the uniform of a captain of the 3rd Battalion of the Gordon Highlanders, in which distinguished corps he served for nearly twenty years. He still has the erect bearing of a soldier.

In the splendid drawing-room, formerly Mr. Goodall’s studio — for the house formerly belonged to Mr. Goodall, R.A. — with its unusual waggon roof, are some of Mr. Gilbert’s choicest possessions, among them an ancient Japanese cabinet, enriched with the choicest decorative work in mother-of-pearl and lacquer, probably one of the finest specimens of Japanese art in the country. A beautiful and delicately decorated grand piano shows how it is possible to deal with this difficult piece of furniture when taste is brought to bear upon the necessary expense. Mr. Gilbert is proud of the perfect acoustic properties of this room, but it is only by asking questions that another interesting fact is elicited, which goes to show how much of the artist exists in a man whose poetic and dramatic genius are well enough known and recognised wherever the English language is spoken. The most striking architectural feature of the drawing-room is a colossal and splendid mantelpiece of carved alabaster, which rises from the floor right up to the spring of the vault of the roof. It is not possible to give an idea of this great work, conceived and executed in the true Renaissance spirit. The conception and the original model in the rough were Mr. Gilbert’s own, carried out artistically by Mr. Ernest George and carved by Mr. Walter Smith. The architrave of the mantelpiece is supported by large terminal caryatid figures of satyrs, and when Mr. Gilbert was posed by THE GRAPHIC photographer, with this fireplace as a background, he remarked upon the immediate propinquity of one of the satyrs that he was sure that our readers would know which was which, adding that he objected to being cut out by his own background.

The library where Mr. Gilbert sat and chatted with us is the abode of the beautiful little ring-tailed lemur, whose portrait, riding, according to the ways of baby lemurs, on his mother’s back, appeared some little time ago in the Daily Graphic. This little animal was actually born and bred upon the estate. Mr. Gilbert tells, with evident pleasure, how its father and mother (who live in the melon-house) were allowed to roam about the grounds in the summer time. "They would come back to feed," he said, "in the cage which was, in fact, a trap as well. When, afterwards, their little one was born, I sent word of the fact to the Zoological Society, and they said it was a remarkable and unique event."

It is not easy to get Mr. Gilbert to talk of his dead friend and colleague, Sir Arthur Sullivan. "We were in agreement on all points connected with our art," he said; "his music for my words, my words for his music. There was never a question between us as to our complete and mutually delightful collaboration. No difficulty ever arose between us in connection with the production of our plays, and when, at one time, the relations between us were a little strained owing to my difference with Mr. D’Oyly Carte, we were always on speaking terms; and it is pleasant to me to remember that a thorough and complete understanding existed between us at the time of his death. It has been assumed that my absence from his funeral was due to another quarrel; but, as a matter of fact, we were on excellent terms, and on the day of his funeral I myself was lying desperately ill at Helonan, near Cairo, from a severe attack of rheumatoid arthritis."

Page modified 24 June 2019