|

|

||||||

He first began to write for the stage in 1865 (29 years of age). His first effort was a burlesque on the “Elisir d’amore,” Donizetti’s famous opera bouffé. The way he first became connected with the stage was that T. W. Robinson, asked by Miss Herbert, then lessee of the St. James’s Theatre, to write her a Christmas piece, found he was too busy to do so, but advised her to apply to MR. GILBERT, who, at her request, undertook to write the piece in ten days. MR. GILBERT within the time agreed upon completed the burlesque, and read it to the company, which included the late Frank Matthews and Miss Carlotta Addison. At the first rehearsal the stage manager, who was none other than Henry Irving, asked the young author did he know anything about stage managing, for he (Irving) was quite inexperienced in the matter. “Well,” said GILBERT, “I have no experience either, but I have my ideas on the subject,” and he accordingly set to work as a novice in what has since become one of his great accomplishments. The piece, produced in such a hurry that there was no time to discuss terms, had a great success, and a fortnight after its production Mr. Emden, the treasurer, asked the author, “Now, what are we to pay you for this piece?” he replied, “Fifty pounds.” “Oh,” said the manager, “Too much; can’t give you more than thirty.” “Very well,” said GILBERT, “let it be thirty.” “Here,” said Mr. Emden, “is your cheque, and if you will oblige me with a receipt, I’ll give you a piece of advice.” The receipt was given, and Mr. Emden said, “The piece of advice is this: Never again sell so good a piece for thirty pounds.” I need scarcely say that the advice was scrupulously followed. The piece ran about a hundred nights, and was followed by burlesques on the “Bohemian Girl,” “La Figlia del Reggimento,” “Norma,” etc.

He then wrote in rapid succession a libretto for Fred Clay, called “A Gentleman in Black,” another called “Princess Toto,” and a number of pieces for German Reed. The first more marked success was a burlesque on Tennyson’s “Princess,” distinguished from the ordinary run of burlesques of that time by more refined dialogue and witty points, the aurora of what afterwards constituted the style so peculiar to W. S. GILBERT. This was followed by “The Palace of Truth,” at the Haymarket, which ran 250 nights; then came “Pygmalion and Galatea,” which ran some 400 nights. “The Wicked World,” which ran 200 nights, was the next comedy. In fact, his series of dramatic works, not quite complete, but very nearly so, runs as follows: “An Old Score,” 1868; “The Princess,” 1869; “The Palace of Truth,” 1870; “Pygmalion and Galatea,” 1871; “Randall’s Thumb,” 1872; “On Guard,” 1873; “The Wicked World,” 1873; “Charity,” 1874; “Tom Cobb,” 1875; and in the same year “Broken Hearts”; “Trial by Jury,” 1876; in the same year “Dan’l Druce” and “Sweethearts”; then “Engaged,” 1877; and “The Sorcerer” and “Pinafore,” 1878; “Gretchen,” 1879; and “The Pirates of Penzance” in 1880; “Patience” in 1881; “Iolanthe,” in 1883; “Princess Ida,” in 1885; “Comedy and Tragedy,” 1885; “Mikado,” 1886; “Ruddigore,” 1888; “Yeomen of the Guard,” 1888, and “Brantinghame Hall,” 1889. His first collaboration with Sullivan was in “Thespis,” produced at the Gaiety in 1873 by Hollingshead, who commissioned them to write a piece together, and therefrom dates the whole series of more or less brilliant successes which constitute the whole library of the Savoy Theatre career, under the Comedy Opera Company, formed by D’Oyly Carte for the purpose of producing the works written by those two renowned authors (1877).

After the production of “H.M.S. Pinafore,” which ran two years, the Comedy Opera Company, Limited, was dissolved, and Mr. D’Oyly Carte built the Savoy Theatre for the express purpose of producing Operas written by SIR A. SULLIVAN and MR. GILBERT, and entered into an arrangement with them for a series, which has now extended over a period of nearly twelve years. “Patience” was the first piece produced under the new regime, and it ran for nineteen months. After “Patience” came “Iolanthe,” which ran fifteen months; then “Princess Ida,” which ran ten months; then the “Mikado,” which ran twenty months; “Ruddigore” which ran ten months, and the “Yeomen of the Guard,” which has already reached its sixth month, and is still running. It is remarkable that a piece of GILBERT’S, “The Vagabond” (1879), for whatever reason, was hooted off the stage, the yelling and shouting being such that not a word of the third act could be heard in the house. This is the black dot on a butterfly’s brilliant wing. Another misfortune befell one of his best pieces. “Foggerty’s Fairy,” which was given with immense effect on the first night at the Criterion, but on the second night the news came of the burning of the Vienna Theatre, which caused such a panic which affected all the London theatres more or less, and as public opinion pointed (most unreasonably) to the Criterion as a theatre from which, if it caught fire, escape would be practically impossible, no one ventured into it, and the piece had to be withdrawn after three weeks’ run.

Two more pieces ought to be mentioned: “Comedy and Tragedy,” designed for Miss Marie Litton, about 13 years ago, but written and completed for Mary Anderson in 1883. Miss Litton asked MR. GILBERT to write her a strong one-act piece; he went away, and between Sloane Square and South Kensington Station the idea of the whole piece flashed upon him. He went home, wrote the “Scenario” out in one hour, came back and laid the piece, so far as it was sketched, before her. Miss Litton, however, feared that the role was too strong for her, and the piece was laid by until Mary Anderson commissioned the author to finish it. The last piece from his pen is “Brantinghame Hall,” which, for reasons not entirely clear, admirably written and admirably acted though it was, was condemned by public and press, and I sincerely hope that MR. GILBERT, enraged at the refusal of an audience to allow him to write other than comic pieces, will not persevere in his rash resolution to withdraw once for ever from writing for the stage.

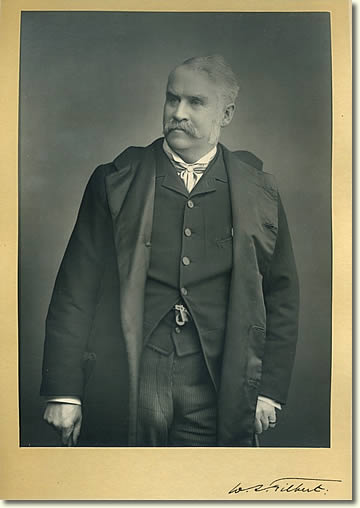

MR. GILBERT is, physically, one of the strongest men I have known – he has never had a day’s illness, he is very moderate in his eating, never drinks wine, rides for a couple of hours every day, is in bed by three in the morning, rarely at half-past two, and invariably up at eight. He passes his time six months of the year in London (Harrington Gardens), in a spacious, beautiful and most tastefully built and decorated house, and the other six months at his country house, Breakspears, which is some 200 years old, and built on the site of the house where the only English Pope (Nicholas Breakspears, otherwise Adrian IV.) was born.

In manners MR. GILBERT is extremely simple, straight to the point; he makes no fuss about himself and stands no nonsense from others. His ability in various directions I have mentioned, and if his pieces, both those written by him alone and the opera in collaboration with Sullivan, have been so successful, a large share of the happy result is due to his incomparable talent of stage managing. I have seen him at rehearsals correct the scene painter, show every actor exactly what to do, and with untiring patience, train the performing soloists and chorus in their duties, until the intended effect was successfully reached. It is one of the conditions that were from the beginning understood by this Comedy Opera Company, that no recourse should be taken to anything that in subject, in costume, or dialogue could give the smallest offence; that no risky jokes should be permitted; that no lady should be allowed to appear in male dress, or indeed, in any costume that a lady might not wear with propriety at a private fancy ball.

The expressed intention of the joint authors when they commenced to write for the Opera Comique in 1877 was to prove that suggestiveness of plot, coarseness of dialogue, and indelicacy of dress, were not as they were then generally supposed to be, essential to the success of Opera bouffé, and the series of unbroken successes achieved at the Opera Comique and Savoy Theatres during nearly twelve years may be taken as proof positive that the authors were right, both in theory and practice. Many of the principal artistes of the Savoy have been nearly twelve years in the Company, and hundreds of young ladies of good social position are waiting for vacancies in the Chorus.

In his conversation MR. GILBERT cannot entirely free himself from the leading principle that guides him in his pieces: Ridendo castigare mores, and it is just a toss up whether he will aim more at the Ridendo or at the castigare, for his satire, always spirituelle and amusing, is sometimes very biting, and it would be too much to expect the bitten one to laugh as the audience does who assist at the castigation. His buoyant spirit, ever ready, can no more help himself satirising than Ovid could help making verses though his father beat him for it, and it is a well-known fact that his apology was itself a Hexameter. MR. GILBERT’S artistic tastes have the support of his full purse, and thus he is enabled to show you in his house a Caracci, Watteau, Rubens, and even a grand Salvator Rosa, etc. Like Offenbach in music, he has found a new genre in Comic Opera, and I very much fear that, like the former, he will find many imitators, but few who attain to his original vigorous genius.

Page modified 31 July 2011