|

|

||||||

Review from

The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News

3 November 1894

“HIS EXCELLENCY” AT THE LYRIC.

Who seeks for jocularities that haven't yet been said.

The world has joked incessantly for over fifty centuries,

And every joke that's possible has long ago been made.

I started as a humourist with lots of mental fizziness,

But humour is a drug which it's the fashion to abuse;

For my stock in trade, my fixtures, and the goodwill of the business

No reasonable offer I am likely to refuse.

Are we to consider these lines—placed as they are in the mouth of a typical exponent of Gilbertian humour, Mr. George Grossmith to wit—as a profession of faith, a spontaneous admission, or is Mr. Gilbert helping us kindly to a compliment? Are we expected to say "Hear, hear," or "No, sir"? As the French say, it gives to think, and though the pretext is not one of great moment, we find it still difficult to solve this particular problem after one solitary hearing of Mr. Gilbert's last contribution to the not overpowering stock of the gaiety of this country. Leaving, however, speculations as to the author's hidden or unrevealed intentions aside, let us proceed with an account pure and simple of the fare provided for the theatre-goers by the "entirely original comic opera" in two acts entitled His Excellency, written by W. S. Gilbert, music composed by Dr. Osmond Carr.

To begin from the beginning, we would suggest that works of a similar kind be called "operettas," the appellation bearing already in itself a clue to the style of the production, musically speaking—taking operetta as diminutive of opera—and also a hint as to the character of the subject submitted for musical treatment. "Comic opera" is a comparatively new term, invented here, and applied with so little discrimination that only good can come of a timely protest for more precision in definitions, otherwise an arrival from the moon, let us say, may be startled to find that the Meistersingers and His Excellency are both spoken of as "comic operas." Taking, then, the last Lyric Theatre production as an operetta we admit with much pleasure that the work has every claim to this appellation, from a musical point of view; Dr. Osmond Carr's music is as much diminutive operatic music as the limits and limitations of the effort will allow. The melodic invention is reduced to its most unpretending, expression, the rhythms are carefully popular, and the orchestration is thoughtfully simple. Altogether, whatever "entirely original" there may be in His ExceIlency is not to be looked for in Dr. Osmond Carr's music. To dwell longer on this part of our account would result only in a chaplet of fault-finding remarks, so that we will take leave here of the music of His Excellency with the expression of a desire that humorous situations and humorous words be henceforth and for ever set only to humorous music. Pardon! we must not forget one really excellent page in the score—the dancing chorus of the soldiers in Act I, with Harold's strophes:

Into your presence I'm made to come

In the contemptibly capacity

Of a confounded teetotum!

This is almost the only instance in which the effect is due in a large degree to the music, the tune being admirably adapted to the words and to the absurdity of the scene, and the irresistible entrain of the rhythm compelling one to mirth and applause without a moment's hesitation. And, of course, we must add in all justice that if Dr. Osmond Carr's music lacks humour it is free from the taint of vulgarity, and that the hand of the expert musician is patent on every step, reaching even a kind of distinction in the choice of harmonies and modulations, and obtaining good effects of sonorities in concerted pieces. Mais c'est tout!

Turning now to Mr. Gilbert's book we will not quarrel with its official qualification as being "entirely original"; we dare say it is, and it is comic into the bargain. It is not the exquisitely funny vein of former productions, and the dimensions are smaller; but still the story has been invented very happily, the incidents hang together extremely well, and though the first act is abnormally long—about five quarters of an hour, like the first act of Lohengrin without cuts—one has hardly the time to feel it, so interesting is the action. The sentimental element has been introduced into it with rare felicity and an admirable sense of proportions, and altogether, as craftsman, Mr. Gilbert comes out exceedingly well from this fresh bid for public favour. This is the story.

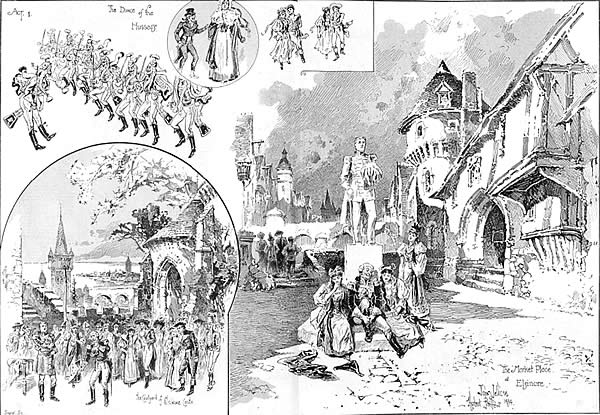

We are at Elsinore, in Denmark, a town, small or big, governed for the Prince Regent by His Excellency Governor George Griffenfeld. The man is an inveterate practical joker, and spends all his time in devising fresh hoaxes, in which he is willingly helped by his two daughters, Thora and Nanna. As the curtain rises on the market square at Elsinore we are introduced at once to the result of one of his practical jokes—a huge marble statue of the Prince Regent, the work of an aspiring young artist, Erling Sykke, who has been led to believe that he was executing a royal commission, and that the reward, besides a sum of money, would be his appointment as sculptor to the court and a countship; Dr. Tortenssen, a young physician, and a friend of the sculptor, has also received welcome news of a patent to be personal physician to the King with the rank of Baron; Dame Hecla Cortlandt, a lady of property and of a considerable number of springs on the wrong side of fifty, caresses fond hopes of a speedy matrimonial union with the Governor; and Mats Munck, Syndic of Elsinore, cherishes identical designs with regard to the lady of property. Of course, these are all His Excellency's practical jokes, only as they seem to have come en suite of a long string of others, complaints have been sent to the King, and the Prince Regent comes in disguise to Elsinore to investigate the state of affairs. The Governor, who has never seen the Prince before, is struck by the likeness of the strolling player—the Prince's disguise—to the statue of the Regent, and decides forthwith to perpetrate the greatest practical joke invented yet. Nils Egilsson—the Prince's assumed name—will personify, for twenty-four hours, the Regent, will receive all complaints, ratify all His Excellency's hoaxing arrangements, and condemn the practical joker to be shot within twenty-four hours. The intrigue is quite clear now, and the dénoument can be guessed; it remains to be added that, amongst other arrangements, the marriage[s] of the sculptor and the physician with the Governor's daughters, Thora, and Nanna, is sanctioned, that the Syndic becomes Governor, His Excellency being merely degraded to the ranks, Dame Cortlandt and everybody else gets married, and the Regent himself finds a love in Christina, it girl who fell in love with his statue. The love-making of these two is the charming sentimental episode mentioned before.

The interpretation of His Excellency can be highly commended as an ensemble performance; but there were some rather lame details. First, in point of view of merit and of spontaneous success, comes Mr. Arthur Playfair, who, as Corporal Harold, fairly took the house by storm, and made the first hit of the evening; true, that his are the funniest situations in the action—Corporal Harold followed by soldiers on to the Market Place dancing, according to the governor's instructions that soldiers should be drilled as ballet girls, and performing afterwards a pas seul—but he made the very best and the very utmost of these situations, winning further distinction as a singer. Next comes Miss Jessie Bond, a genuine opera bouffe starlet, who makes a delightfully whimsical Nanna; Mr. John Le Hay as the Syndic is very good, but there is a kind of sameness in every new part this clever actor plays. Mr. Augustus Cramer as the physician is a better actor and singer than Mr. Charles Kenningham as the sculptor. Mr. Rutland Barrington as the Prince Regent, and Mr. George Grossmith as His Excellency, do, of course, admirably what they have to do, but they have not enough "business" to display their particular gifts to advantage. Miss Ellaline Terriss as Thora looks very dainty, only a smile, however charming, is not an equivalent of genuine fun and drollery, and beautifully smiling Thora sadly lacks both. Miss Alice Barnett as Dame Hecla Cortlandt makes energetic and, at times, successful efforts to raise laughter, and Miss Gertrude Aylward is a sufficiently vivacious Vivandière. There is finally Miss Nancy McIntosh as Christina, the ballad singer; a certain amount of expectation has been raised by the appearance of the young lady, and such as were realised do not warrant any excessive enthusiasm. The voice of Miss McIntosh is very fragile, the three qualities of sound, pitch, power, and timbre, not being always exactly in proper relationship; the style of singing is of a rather primitive kind and the acting is somewhat amateurish but we noticed, with as much pleasure as astonishment, that Miss McIntosh possesses a distinct dramatic instinct. She has a rather long soliloquy in act first before the statue, and a scene afterwards with the Regent, both situations of no mean difficulty, and in which Mr. Gilbert has put some of his most refined prose; well, Miss McIntosh said her lines to perfection, with a beautifully ringing speaking voice, delightfully modulated and well managed, and as long as there was no demand on gestures or motion in general, the sight of the dainty girlish figure making love to a marble statue was fascinating to a degree. We would have fain encored this scene, and we commend it to the attention of our readers. The composer conducted an admirable orchestra.

It is almost needless to add that a right royal welcome was afforded to all concerned in this production, which was enthusiastically received, and the mounting and staging of His Excellency are irreproachable.

Our picture shows the finale of the first act, in which all other characters having danced off, the Governor and his two daughters are left at the base of the statue in great glee at the success of the sham Regent joke. From the second act is the scene where the Egent degrades the practical joker to the ranks. Elsewhere is a scene between the Widow Cortlandt and Max Monck, the Syndic.

JEAN SANS PEUR

|

Page modified 20 October 2020