|

|

||||||

From "The Graphic", 3 November 1894, p. 519

The new comic opera, His Excellency, which was produced at the Lyric Theatre on Saturday night, is the first effort of Mr. Gilbert in association with Dr. Osmond Carr, the composer of the incidental music to Morocco Bound and other fugitive works. That even Dr. Carr could quite reconcile us to the—it is hoped only temporary—suspension of the artistic partnership between Mr. Gilbert and Sir Arthur Sullivan was hardly to be expected. On the other hand, it would be grossly unfair to compare a musician who is almost a neophyte in light opera with Sir Arthur Sullivan, who was practically the inventor of this species of musical satire. Nevertheless, a certain sense of disappointment can hardly be denied. Dr. Carr has for the most part taken Sullivan as his model, and the imitation, unconscious though it may be, is devoid of the best features of the original. Sir Arthur has a strong idea of the comic in music; Dr. Carr has not. Sir Arthur’s orchestration is remarkable for many a delicate touch, whether of finish or of humour; whereas Dr. Carr is, as a rule, content either to accompany his songs in a manner which would be equally effective on a pianoforte, or he makes vigorous use of the bass and side drum. Dr. Carr must, however, be credited with a gift of tunefulness and vivacity, and sometimes, as, for instance, in the finale to the first act, he shows that he is capable of far better things.

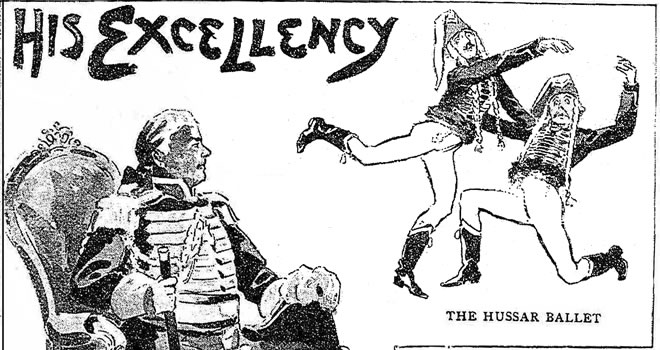

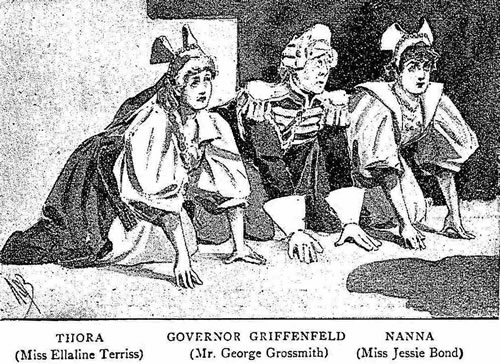

As to the libretto, to say that it is by Mr. Gilbert is sufficient to indicate that it is an excellent piece of topsy-turvy foolery, and that it is full of whimsicalities, satire, and witticisms. Some of the dialogue, may perhaps, [sic] not be quite as smart as that of his own former works, but it is at any rate a very agreeable contrast to most of the comic operas which we import from France. The story deals with the practical joke of the Governor of Elsinore, who has given a bogus order for a statue to the young sculptor, has pretended to ennoble a young physician, and at last persuades a strolling player to impersonate the Regent, and shower sham dignities upon the people. “Fancy,” he says, “a sham Regent dispensing sham wealth and sham honours untold to all my sham friends, and then their disappointment when they discover that it is only my fun.” The Governor’s two mischievous daughters enter thoroughly into the spirit of the hoax, and persuade the two young men that they will marry them when their fancied honours are confirmed. In the result, the strolling player proves to be the Regent in disguise, and thus the practical jokes recoil on the Governor himself, who is reduced to the ranks, and in the uniform of a private in the fortress which he once commanded, presents arms as the curtain falls. It is, however, in points of detail that Mr. Gilbert is most in his element. Nothing, for example, can be better than the idea of the ballad singer Christina, who falls in love with the statue of the Regent, and addresses the stone in the prettiest of mock Shakesperian [sic] speeches. Again, the notion of a troop of Hussars, whom the Governor compels to drill like ballet girls, is excessively funny, and no heartier laughter has occurred in any of Mr. Gilbert’s operas than that which greeted on Saturday the scene of the ballet danced by these soldiers, who form themselves into groups, while their corporal pirouettes round them on his toes. In vain the officer remonstrates:—

| Oh you may laugh at our dancing-schoolery, | |

| It’s all very well, it amuses you; | |

| But how would you like this dashed tomfoolery | |

| Every day from ten to two? | |

On the other hand, the love episodes of the old woman are a trifle monotomous, and her continual struggle between “two Tremendous Powers in perpetual antagonism — a Diabolical Temper and an Iron Will”—become wearisome. The two funniest songs in the piece are those in which the Governor and his daughters descant upon the joys of a practical joke:—

And turnip-heads on posts make very decent ghosts;

Then hornets sting like anything when placed in waistcoat pockets.

and Mr. Grossmith’s lament that he did not live in the time when all witticisms were new:—

The door mat from the scraper, is it distant very far?

And when no one knew where Moses was when Aaron put the candle out,

And no one had discovered that a door could be a-jar.

On the other hand, as in the fable of the “Magnet and The Silver Churn,” in a previous opera, the satire is more subtle in the “Bee Song,” which Christina, accompanying herself on the guitar, sings at the opening of the second act:—

| That hive contained one obstinate bee (His name was Peter), and spake he: |

||

| “Though every bee has shown white feather, | ||

| To bow to fashion I am not prone; | ||

| Why should a hive swarm all together? | ||

| Surely a bee can swarm alone?” | ||

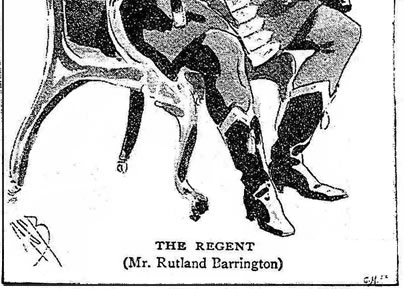

In this merry fashion does the opera continue through one rather long first act, and a shorter and much inferior second act, the vocal music being entrusted to a couple of pairs of lovers, that is to say the Governor’s two daughters, parts admirably paired by Miss Jessie Bond and Miss Ellaline Terriss, and a sculptor and a physician, enacted in manly fashion by Mr. Kenningham and Mr. Cramer. Miss M’Intosh, although somewhat out of voice on Saturday, sang with much taste the opening address to the statue, and the bee song in the second act, while although she needs a little more animation, and her dancing is open to considerable improvement, she played this graceful character with much charm. Mr. John le Hay, as the senile Syndic, and Miss Alice Barnett, as Dame Hecla, an ancient lady betrothed to the Governor, had conventional parts with which they could do comparatively little. On the other hand Mr. Arthur Playfair was admirable as the dancing Corporal of Hussars, and Mr. Rutland Barrington enacted to the life the rôle of the Prince Regent, disguised as a strolling player, who finds Elsinore by no means stage struck, and eventually aspires to “Play Hamlet on his native battlements.”

Page modified 22 October 2020