The Story of H.M.S. Pinafore

by Sir W. S. GilbertGo to a PDF version of this chapter.

THE STORY OF

H.M.S. PINAFORE

BY

SIR W. S. GILBERT

ILLUSTRATED IN COLOUR AND BLACK AND WHITE BY

ALICE B. WOODWARD

LONDON

G. BELL AND SONS, LTD.

1913

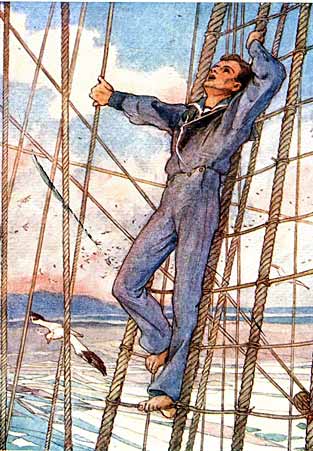

Ralph Rackstraw in

the rigging.

TO MY YOUNG READERS

I HAVE been asked to explain to you how it comes to pass that this, the story of a well-known Play, is now placed before you in the form of a Tale. In the first place, many very young ladies and gentlemen are never taken to the Theatre at all. It is supposed by certain careful Papas and Mamas that very young ladies and gentlemen should go to bed at an early hour, and that it is very bad for them to sit up as late as half past eleven or twelve o'clock at night. Of course, this difficulty could be overcome by taking them to Morning Performances, which are so called because they invariably take place in the afternoon; but there are drawbacks even to Morning Performances. Unless you are seated in the front row of the stalls (where the band is sure to be too loud), or in the front row of the dress circle (which is a long way off), the enjoyment of very young ladies and gentlemen is pretty nearly sure to be interfered with by the gigantic cart-wheel hats, decorated with huge bunches of wobbling feathers that ill-bred and selfish ladies clap upon their heads, nowadays, whenever they go to a theatre in the daytime. A third reason (and perhaps the best of them all) is that very young ladies and gentlemen find it rather difficult to follow the story of a play, much of which is told in songs set to beautiful music, and all of which is written in language which is better suited to their Papas and Mamas than to themselves. A fourth reason (but this is not such a good one as the other three) is that the Opera upon which this book is founded is, unhappily, not played in every town every night of the year. It should be, of course, but it is not, and it may very well happen that some poor people have to go so long as two or three years without having any opportunity of improving their minds by seeing it performed. When we get a National Theatre, at which all the best plays will be produced at the expense of the Public (who will also enjoy the privilege of paying to see the Plays after they have defrayed the cost of producing them), "Her Majesty's Ship Pinafore" will, no doubt, be played once or twice in every fortnight for ever; but as some years must elapse before this happy state of things can come to pass, and as those who are very young ladies and gentlemen now may be very middle-aged ladies and gentlemen then, it was thought that it would be a kind and considerate action to supply them at once with a story of the Play, so as not to subject them to the tantalizing annoyance of having to wait (possibly) many years before they have an opportunity of learning what it is all about.

As I would not for the world deceive my young readers, I think it right to state that this story is entirely imaginary. It might very well have happened but, in point of fact, it never did.

GREAT BRITAIN is (at present) the most powerful maritime country in the world; she possesses a magnificent Fleet, superb officers and splendid seamen, and one and all are actuated by an intense desire to maintain their country's reputation in its highest glory.

One of the finest and most perfectly manned ships in that magnificent Fleet was Her Majesty's Ship Pinafore, and I call the ship "Her Majesty's" because she belonged to good Queen Victoria's time, when men-of-war were beautiful objects to look at, with tall tapering masts, broad white sails, and gracefully designed hulls; and not huge slate-coloured iron tanks without masts and sails as they are to-day. She was commanded by Captain Corcoran, R. N., a very humane, gallant, and distinguished officer, who did everything in his power to make his crew happy and comfortable. He had a sweet light baritone voice, and an excellent ear for music, of which he was extremely fond, and this led him to sing to his crew pretty songs of his own composition, and to teach them to sing to him. To encourage this taste among his crew, he made it a rule on board that nobody should ever say any-thing to him that could possibly be sung— a rule that was only relaxed when a heavy gale was blowing, or when he had a bilious headache. Harmless improving books were provided for the crew to read, and vanilla ices, sugar-plums, hardbake and raspberry jam were served out every day with a liberal hand. In short, he did everything possible (consistently with his duty to Her Majesty) to make everybody on board thoroughly ill and happy.

Captain Corcoran was a widower with one daughter, named Josephine, a beautiful young lady with whom every single gentleman who saw her fell head-over-ears in love. She was tall, exquisitely graceful, with the loveliest blue eyes and barley-sugar coloured hair ever seen out of a Pantomime, but her most attractive feature was, perhaps, her nose, which was neither too long nor too short, nor too narrow nor too broad, nor too straight. It had the slightest possible touch of sauciness in it, but only just enough to let people know that though she could be funny if she pleased, her fun was always gentle and refined, and never under any circumstances tended in the direction of unfeeling practical jokes. It was such a maddening little nose, and had so extraordinary an effect on the world at large that, whenever she went into Society, she found it necessary to wear a large pasteboard artificial nose of so unbecoming and ridiculous a description that people passed her without taking the smallest notice of her. This alone is enough to show what a kind-hearted and self-sacrificing girl was the beautiful Josephine Corcoran.

One of the smartest sailors on board Her Majesty's Ship Pinafore was a young fellow called Ralph Rackstraw, though, as will be seen presently, that was not his real name. He was extremely good-looking, and, considering that he had had very little education, remarkably well-spoken. Unhappily he had got it into his silly head that a British man-of-war's man was a much finer fellow than he really is. He is, no doubt, a very fine fellow indeed, but perhaps not quite so fine a fellow as Ralph Rackstraw thought he was. He had heard a great many songs and sentiments in which a British Tar was described as a person who possessed every good quality that could be packed into one individual, whereas there is generally room for a great many more good qualities than are usually found inside any sailor. A good packer never packs anything too tight; it is always judicious to leave room for unexpected odds and ends, and British Tars are very good packers and leave plenty of room for any newly acquired virtues that may be coming along. So, although Ralph had gathered up many excellent qualities, there were still some that he had not yet added to his collection, and among these was a proper appreciation of the fact that he hadn't got them all. In short, his only fault was a belief that he hadn't any.

Ralph Rackstraw was one of the many who loved Josephine to distraction. Nearly all the unmarried members of the crew also loved Josephine, but they were older and more sensible than Ralph, and clearly understood that they could never be accepted as suitable husbands for a beautiful young lady of position, who was, moreover, their own Captain's daughter. They knew that their manners were quite unsuited to polite dining and drawing-rooms, and indeed they would have been very uncomfortable if they had been required to sit at table with gentlemen in gold epaulettes, and ladies in feathers and long trains; so they very wisely reasoned themselves into a conviction that the sooner they put Josephine out of their heads the better it would be for their peace of mind.

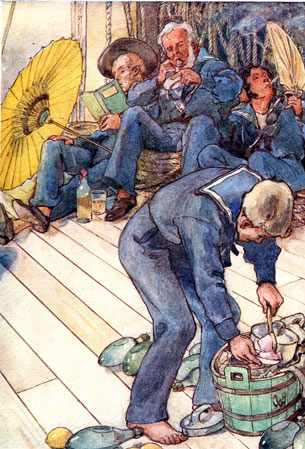

There is a time, between four and six in the after-noon, when the men-of-war sailors are allowed to cease their work and amuse themselves with cheerful songs and rational conversation. It is called the "dog-watch" (why, I can't imagine), and at that time all who are not engaged upon any special duty meet on the forecastle (which is the front part of the upper deck) to sing pretty songs and tell each other those harmless but surprising anecdotes which are known in the Royal Navy as "yarns." One of the most popular subjects of conversation during the dog-watch on board the Pinafore was the kindness and consideration shown by their good Captain Corcoran towards the men under his command, and another was the agreeable fact that the Pinafore was one of those jolly ships that never pitched and rolled, and consequently never made any of the sailors sea-sick. The crew, who had been carefully trained by Captain Corcoran to sing more or less in tune, always opened the dog-watch with this chorus:

We sail the ocean blue,

And our saucy ship's a beauty!

We're sober men and true

And attentive to our duty.

When the balls whistle free o'er the bright blue sea,

We stand to our guns all day;

When at anchor we ride on the Portsmouth tide

We've plenty of time to play!

This they used to sing as they sipped their ices, and ate their rout-cakes and almond toffee. The song might strike you at first as rather too complimentary to themselves, but it was not really so, as each man who sang it was alluding to all the others, and left himself out of the question, and so it came to pass that every man paid a pretty compliment to his neighbours, and received one in return, which was quite fair and led to no quarrelling.

As the sailors sat and talked they were joined by a rather stout but very interesting elderly woman of striking personal appearance. She was what is called a "bum-boat woman," that is to say, a person who supplied the officers and crew with little luxuries not included in the ship's bill of fare. Her real name was Poll Pineapple, but the crew nick-named her "Little Buttercup," partly because it is a pretty name, but principally because she was not at all like a buttercup, or indeed anything else than a stout, quick-tempered, and rather mysterious lady, with a red face and black eyebrows like leeches, and who seemed to know something unpleasant about every-body on board. She had a habit of making quite nice people uncomfortable by hinting things in a vague way, and at the same time with so much meaning (by skilful use of her heavy black eyebrows), that they began to wonder whether they hadn't done something dreadful, at some time or other, and forgotten all about it. So Little Buttercup was not really popular with the crew, but they were much too kind-hearted to let her know it.

Little Buttercup had a song of her own which she always sang when she came on board. Here it is:

I'm called Little Buttercup — dear Little Buttercup,

Though I could never tell why,

But still I'm called Buttercup — poor Little Buttercup,

Sweet Little Buttercup, I.

I've ribbons and laces to set off the faces

Of pretty young sweethearts and wives.

I've treacle and toffee and very good coffee,

"Soft Tommy" and nice mutton chops,

I've chickens and conies and dainty polonies

I've snuff and tobaccy and excellent "Jacky,"

I've scissors and watches and knives,

And excellent peppermint drops.

Then buy of your Buttercup — dear Little Buttercup,

Sailors should never be shy

So, buy of your Buttercup — poor Little Buttercup

Come, of your Buttercup buy!

"Thank goodness, that's over!" whispered the sailors to each other with an air of relief. You see, Little Buttercup always sang that song whenever she came on board, and after a few months people got tired of it. Besides not being really popular on account of her aggravating tongue, she sold for the most part things that the liberal Captain provided freely for his crew out of his own pocket-money. They had soup, fish, an entrée, joint, an apple pudding, or a jam tart every day, besides eggs and ham for breakfast, muffins for tea, and as many scissors, pocket-knives, and cigars as they chose to ask for. So Little Buttercup was not even useful to them, and they only tolerated her because they were gallant British Tars who couldn't be rude to a lady if they tried. In point of fact they had tried on several occasions to say rude and unpleasant things to ladies, but as they had invariably failed in the attempt they at last gave it up as hopeless, and determined to be quietly polite under all possible circumstances. So they asked her to sit down, and take a strawberry ice and a wafer, which she did rather sulkily as no one seemed to want any of the things she had to sell.

"Tell us a story, Little Buttercup," said Bill Bobstay. Bill was a boatswain's mate, who, be-sides being busily occupied in embroidering his name in red worsted on a canvas "nighty case," generally took the lead in all the amusements of the dog-watch. "You can if you try, I'm sure, Miss."

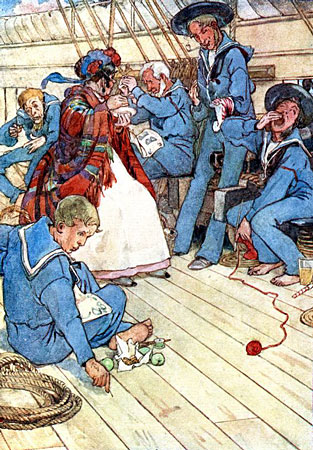

"You're quite right," said Little Buttercup; I could tell you stories about yourselves which would make you all wish you had never been born. I know who takes sugar-plums to bed with him" (looking at one), "and who doesn't say his prayers" (looking at another), "and who sucks his thumb in his hammock" (looking at the third), "and who makes ugly faces at his Captain when his back's turned" (looking at a fourth), "and who does his front hair with patent curlers "(looking at a fifth)," and who puts raspberry jam into his messmates' boots" (looking at a sixth).

All the sailors referred to looked very hot and uncomfortable, for their consciences told them that Little Buttercup had hit off their various weaknesses with surprising accuracy.

"Let's change the subject," said Bill Bobstay (he was the one who ate sugar-plums in bed), "we all have our faults. But, after all, we're not so bad as poor Dick Deadeye — that's one comfort!"

I know who takes sugar-plums to bed with him.

Now this was very unjust on the part of Mr. Bobstay. Dick Deadeye, who sat apart from the others, busy manicuring his nails, was one of the ugliest persons who ever entered the Navy. His face had been so knocked about and burnt and scarred in various battles and from falling down from aloft, that not one feature was in its proper place. The wags among the crew pretended that his two eyes, his nose, and his mouth, had been playing "Puss in the Corner," and that his left eye, having been unable to find a corner that was unoccupied, was consequently left in the middle. Of course this was only their nonsense, but it shows what a very plain man he must have been. He was hump-backed, and bandy-legged, and round-shouldered, and hollow-chested, and severely pitted with small-pox marks. He had broken both his arms, both his legs, his two collar-bones, and all his ribs, and looked just as if he had been crumpled up in the hand of some enormous giant. He ought properly to have been made a Greenwich Pensioner long ago, but Captain Corcoran was too kind-hearted to hint that Dick Dead-eye was deformed, and so he was allowed to continue to serve his country as a man-o'-war's man as best he could. Now Dick Deadeye was generally disliked because he was so unpleasant to look at, but he was really one of the best and kindest and most sensible men on board the Pinafore, and this shows how wrong and unjust it is to judge unfavourably of a man because he is ugly and deformed. I myself am one of the plainest men I have ever met, and at the same time I don't know a more agreeable old gentleman. But so strong was the prejudice against poor Dick Deadeye, that nothing he could say or do appeared to be right. The worst construction was placed upon his most innocent remarks, and his noblest sentiments were always attributed to some unworthy motive. They had no idea what the motive was, but they felt sure there was a motive, and that he ought to be ashamed of it.

Dick Deadeye sighed sadly when Mr. Bobstay spoke so disparagingly of him. He wiped a tear from his eye (as soon as he had found that organ), and then continued to manicure his poor old cracked and broken nails in silence.

"What's the matter with the man?" said Little Buttercup; "isn't he well?"

"Aye, aye, lady," said Dick, " I'm as well as ever I shall be. But I am ugly, ain't I?"

"Well," said little Buttercup, "you are certainly plain."

"And I'm three-cornered, ain't I?" said he. "You are rather triangular."

"Ha! ha!" said Dick, laughing bitterly. "That's it. I'm ugly, and they hate me for it!"

Bill Bobstay was sorry he had spoken so unkindly.

"Well, Dick," said he, putting down his embroidery, "we wouldn't go to hurt any fellow creature's feelings, but, setting personal appearance on one side, you can't expect a person with such a name as 'Dick Deadeye' to be a popular character — now, can you?"

"No," said Dick, sadly, " it's asking too much. It's human nature, and I don't complain!"

At this moment, a beautiful tenor voice was heard singing up in the rigging:

The Nightingale

Loved the pale moon's bright ray

And told his tale

In his own melodious way,

He sang, "Ah, Well-a-day!"

The lowly vale

For the mountain vainly sighed;

To his humble wail

The echoing hills replied,

They sang, "Ah, Well-a-day!"

"Who is the silly cuckoo who is tweetling up aloft?" asked Little Buttercup, rather rudely, as she scooped up the last drops of her ice.

"That?" said Bobstay, "Why, that's only poor Ralph Rackstraw who's in love with Miss Josephine."

"Ralph Rackstraw!" exclaimed little Buttercup, "Ha! I could tell you a good deal about him if I chose. But I won't — not yet!"

At this point Ralph descended the rigging and joined his messmates on deck.

"Ah, my lad," said one of them, "you're quite right to come down — for you've climbed too high. Our worthy Captain's child won't have nothing to say to a poor chap like you."

All the sailors said "Hear, hear," and nodded their heads simultaneously, like so many china mandarins in a tea-shop.

"No, no," said Dick Deadeye, "Captains' daughters don't marry common sailors."

Now this was a very sensible remark, but coming from ugly Dick Deadeye it was considered to be in the worst possible taste. All the sailors muttered, "Shame, shame!"

"Dick Deadeye," said Bobstay, "those sentiments of yours are a disgrace to our common nature."

Dick shrugged his left eyebrow. He would have shrugged his shoulders if he could, but they wouldn't work that way; so, always anxious to please, he did the best he could with his left eyebrow, but even that didn't succeed in conciliating his messmates.

"It's very strange," said Ralph, " that the daughter of a man who hails from the quarter deck may not love another who lays out on the fore-yard arm. For a man is but a man, whether he hoists his flag at the main-truck, or his slacks on the main deck."

This speech of Ralph's calls for a little explanation, for he expressed himself in terms which an ordinary landsman would not understand. The quarter deck is the part of the ship reserved for officers, and the fore-yard arm is a horizontal spar with a sail attached to it, and which crosses the front mast of a ship, and sailors are said to "lay out" on it when they get on to it for the purpose of increasing or reducing sail. Then again, the main-truck is the very highest point of the middle mast, and it is from that point that the Captain flies his flag, while a sailor is said to "hoist his slacks" when he hitches up the waist-band of his trousers to keep them in their proper place. Now you know all about that.

"Ah," said Dick Deadeye, "it's a queer world!"

"Dick Deadeye," said Mr. Bobstay, "I have no desire to press hardly on any human being, but such a wicked sentiment is enough to make an honest sailor shudder."

And all his messmates began to shudder violently to show what honest sailors they were and how truly Bobstay had spoken; but at that moment the ship's bell sounding four strokes gave them notice that the dog-watch had come to an end. So the crew put away their manicure boxes and embroidered "nighty cases" and dispersed to their several duties.

Page updated 19 August, 2011