|

|

||||||

INTRODUCTION

"Offenbach there at last!" was Sullivan's cry in his diary when The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein appeared at the Savoy Theatre in December 1897. Of all the theatres in London, the Savoy had been founded with the express purpose of promoting English comic opera in opposition to French operetta — in particular Offenbach. To bring the work of this composer to this most British of British stages was daring.

It was equally daring to produce a work that was both well-known and risque. The plot of the opera hinges on the interests of the title character for Fritz, a well-endowed young private. This interest was slightly toned down from the original, but it remains fairly blatant. In all its years, the Savoy had shied away from such fare, but the appeal of The Grand Duchess for Richard D'Oyly Carte may have been the opportunity to combat the steadily ascending popularity of modern musical comedy with its doubles entendres and overt flirtation. That there was no risk involved in producing something unknown may have been equally appealing.

La Grande-Duchesse de Gerolstein was first produced at the Varietes, Paris, on April 12, 1867, where Hortense Schneider played the title role to tremendous acclaim. Seven months after its Paris debut, the opera appeared at Covent Garden in a translation by Charles Kenney. This translation became standard and was used in productions and revivals throughout England and the United States.

For the Savoy's production, Richard D'Oyly Carte commissioned a new translation from librettist Charles Brookfield and lyricist Adrian Ross. This was Brookfield's first assignment for the Savoy, limited though it was to the dialogue. He was also responsible for the dialogue of the Savoy's other translation/rewrite from the French, The Lucky Star (1899) based on Chabrier. Ross had written new lyrics for Messager's Mirette in its second incarnation (October 1894) and would also contribute lyrics to The Lucky Star.

Like any work with a 30-year history, The Grand Duchess of Gerolstein had its share of traditions. Some of these were certainly mocked, but not all of these I am familiar with. The leap-frog scene at the end of Act II seems to be one of them, but most obvious is the effeminacy of Prince Paul, previously a more robust romantic prince. The Chronique de la Gazette de Hollande became a skit on "society" papers.

Some plot elements were changed, most particularly at the end. In the original, Fritz's thrashing came at the hand of General Boum's lover's husband. At the Savoy, the conspirators arrange for the beating to look like it came from Prince Paul. The Savoy may have been opening its doors to a different type of comic opera, but it was not going to sink to bringing extramarital affairs to its hallowed stage.

Whatever the glories of Offenbach, the orchestration was deemed insubstantial for late nineteenth century British tastes. It was strengthened by Ernest Ford, the composer of the Savoy's Jane Annie.

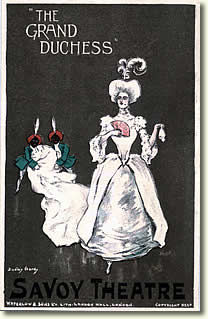

Florence St. John, one of the premier musical comedy actresses of the age, took the title role and the Savoy's contract tenor Charles Kenningham played Fritz. The part of Wanda would be the last role Florence Perry, the Savoy's contract soprano, created for D'Oyly Carte. Comedy was supplied by Walter Passmore as the blustering General Boum, Henry Lytton as the effeminate Prince Paul, William Elton as the crafty Baron Puck, and Brookfield himself as the imperturbable Baron Grog. Despite this impressive cast and the name of Offenbach on the title page, the Savoy's Grand Duchess lasted only 99 performances. The first revival of The Gondoliers filled the gap while Sullivan's latest Savoy offering, The Beauty Stone, went through final preparations for its premiere in May 1898.

- Notes on the text by Clifton Coles

- Libretto (text file)

- Vocal Score (PDF File)

- Review from The Times, 6 December 1897

- Programme from the Savoy Theatre

- Illustrated Music Covers

Page modified 23 August 2011