|

You are here:

>

>

>

>

Introduction

The Window Background Notes by Paul Howarth The suggestion that Tennyson and Sullivan should collaborate on a collection of songs was originally made by George Grove, the secretary of the Crystal Palace, a friend of Sullivan and early champion of his music. At the time, a sequence of songs linked by a narrative, like Schubert's Die Schöne Müllerin but in English, was a novelty. Grove sent Tennyson some verses by Heine to inspire him and from the outset it was intended that Millais would illustrate the poems when the work was published. Clearly, the composition of a work in which he was following the example of Schubert and Schumann and the association of his name with that of Tennyson would have appealed strongly to the ambitious young Sullivan. Initially Tennyson was also enthusiastic about the project and on 17 October 1866 Sullivan and Grove visited Tennyson at his home at Freshwater on the Isle of Wight. Grove gives an account of this visit in a letter:1 I had proposed to [Tennyson] to write a Leiderkreis for Sullivan to set and Millais to illustrate...Sullivan went down with me, and pleased Mr. and Mrs Tennyson extremely. In the evening we had as much music as we could on a very tinkling piano, very much out of tune, and then retired to his room at the top of the house where he read us the three songs, a long ballad, and several other things; and talked till two o'clock in a very fine way about the things which I always get round to sooner or later – death and the next world, and God and man etc.

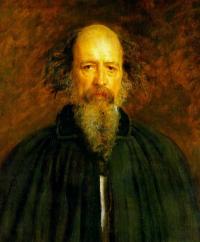

On several occasions, Tennyson visited Sullivan at his home in Claverton Terrace, Pimlico to discuss the project. Sullivan later recalled one occasion: 2 The first time Tennyson came to dine at my house, the door was opened to him by a parlour-maid who had been with us many years and was like one of the family. She was fairly staggered by the appearance of the visitor, who, as will be remembered, always wore a deep, broad-brimmed black felt hat and a black cape or short cloak, which made him look exactly like a conspirator in an Italian or Spanish play. Our little party consisted of Tennyson, Millais, Francis Byng (now Earl of Stafford), myself, my mother and another lady. We met to discuss the proposed work in collaboration which afterwards was published as 'The Window; or, the Loves of the Wrens'. [sic.] When the guests had departed, Kate, the maid, said to me, "Was that really the great poet, Master Arthur?" (I was nearly thirty!) "Well! he do wear clothes!" "Of course," I replied with subtle irony, "all poets do. Besides," I added, "you forget that he is Poet-Laureate." She hadn't forgotten it, for she never had known it. Then after a slight pause, she said thoughtfully: "What a queer uniform!" Now, I wonder if she imagined that Tennyson belonged to a brigade all dressed in the same way. Francis Byng also recalled the occasion: I was present, by his Invitation, at a Dinner when he, Tennyson and Millais dined together at his house. Tennyson read The Window – Song of the Wren Millais gave his notions of the Illustrations suitable – Sullivan suggesting the Music – An unique pleasure and privilege – I suggested to A. S. that I represented 'Ignorance' of all three – Poetry, Music and Art. 3 On 5 February 1867, Emily Tennyson wrote to Sullivan inviting him to visit Tennyson again at his house the following Saturday, extending the invitation to Grove also.4 But, by this time it seems Tennyson was beginning to have doubts about his contribution to the project. Sullivan gives an account of this visit in a letter he wrote home from Tennyson's house on 10 February: When I got here I had a cup of tea and then went and smoked with Tennyson until dinner time. He read me all the songs (twelve in number), which are absolutely lovely, but I fear there will be a great difficulty in getting them from him. He thinks they are too light, and will damage his reputation, &c. All this I have been combating, whether successfully or not I shall be able to tell you tomorrow. 5 Sullivan did succeed in getting the verses from Tennyson and on 7 August, Bertrand Payne, on behalf of the publisher Strahan, wrote to Sullivan to say that Tennyson had completed the task of revising the words and enquiring how long Sullivan would need to compose the music and wondering whether Millais would have the illustrations ready in time for publication by February 1868.6 In the event, it was Tennyson's procrastination which delayed publication. For years he argued strenuously that the songs should not be published, saying that the scheme would damage his reputation or that the time was not propitious. At one point, he apparently offered Sullivan the sum of £500 to abandon the project.7 Eventually, Tennyson gave way and on 6 November 1870 wrote to Strahan: 8 'He that swearest to his neighbour and disappointeth him not' – so I must consent to the publication of the songs, however much against my inclination and judgement, and that I may meet your wishes as to the time of publication, I must also consent to their being published this Xmas, however much more against my inclination and judgement – provided, as I stated yesterday that the fact of their having been written four years ago, and of their being published by yourself, be mentioned in the preface, also that no one but Millais shall illustrate them. By this time, however, Millais had allowed the drawings he had prepared to be dispersed and had explained to Sullivan in a letter dated 19 August that it was really impossible for him to undertake the matter again. He continued: I am very sorry, as of course I should have liked to have carried out the original idea. You must remember that I did keep the drawings for months before they were parted with. One line from him (Tennyson) at the time would have saves the trouble.9 The songs were finally published early in 1871 with a single illustration by Millais and the following preface by Tennyson: Four years ago Mr. Sullivan requested me to write a little song-cycle, German fashion, for him to exercise his art upon. He had been very successful in setting such old songs as Orpheus with his lute, and I drest up for him, partly in the old style, a puppet, whose almost only merit is, perhaps, that it can dance to Mr. Sullivan's instrument. I am sorry that my four year old puppet should have to dance at all in the dark shadow of these days; but the music is now completed, and I am bound by my promise. (Tennyson's reference to "the dark shadow of these days" is an allusion to the Franco-Prussian War) The volume was handsomely produced in both green and dark maroon cloth boards, gilt blocked and with gilt edges. The twelve poems by Tennyson, of which Sullivan had set eleven, were printed separately at the front as well as underlying the music. One of the poems which Sullivan had set had been subsequently revised by Tennyson and was printed there in its "corrected" form as though in contradiction to Sullivan's setting of the earlier version. Sullivan was upset by Tennyson's preface: he felt it was both unnecessary and unkind and complained to Tennyson. The poet eventually replied: I have been some time in answering your note because I have been asking several friends who had already seen my little preface to the Songs of the Wrens, what their impression of it was. They had all failed to see in it the slightest kind of unfriendly allusion to yourself, and took it only as an expression of my own regret at the unappropriateness of the time of publication, and even that my words were not worthy of your music. You may feel certain that there was and is no intention on my part to give the public any other impression; and you cab, if you choose, let all you chaffing friends of the Club know that you have this under my hand and seal. 10 This was sufficient to restore friendly relations between the poet and the composer. Tennyson had surely been right to worry that the public might find some of his verses banal, and, according to Arthur Jacobs, Sullivan's inspiration also flagged. Whilst he allows that the first song has a rich promise not only in atmosphere but in possibilities of thematic development through the whole cycle, the later songs settle for static, obvious expression.11 However, David Selwyn, in the notes which accompanied the only recent commercially available recording of the songs 12 , writes of Sullivan's remarkable variety of musical expression 'from the dramatic opening in "The lights and shadows fly", with its swirl of agitated arpeggios, to the tenderly knowing complicity of "Where is another"; and in the last song, the sudden moment of insight contained in the question "O heart, are you great enough to love?" is answered conclusively by music of much assuredness as to amount to affirmation.' A more modest edition than the first was published in 1900 13 , after Tennyson's death, by Joseph Williams. A new feature of this edition was the addition of a German text, translated from Tennyson by Willy Kastner. Millais illustration was absent, as was Tennyson's preface. Instead, there is the following note by Sullivan: This Song-cycle was written by the late Lord Tennyson at my request and set to music by me in 1869-70. It was to be illustrated by the late Sir John Millais R.A. so that the work might form a combination of Poetry, Painting and Music: but for reasons unnecessary to enter into here, the drawings were never completed, and after various delays the words and music only were published as an Album in 1871. – Paul Howarth Notes.

Page modified 29 July 2007

|

|||||||||