You are here: > > The Making of "The Sorcerer"

by François Cellier, Savoy Musical Director

- Selection of principal artists

- Gilbert's musical knowledge

- George Grossmith

- Mrs. Howard Paul

- Rutland Barrington

- Richard Temple

- Original cast of The Sorcerer

- Press opinions

- Dora's Dream

- The Spectre Knight

But as regards Gilbert and Sullivan it may honestly be affirmed that, from first to last, throughout their long association, they seldom found occasion for any serious controversy concerning the suitability of an artist for the part to be assigned.

During the process of building, like wise architects, our author and composer held continued conference over every detail of the structure in hand. From basement to roof every Sullivanesque bar and every Gilbertian bolt was jointly tested and mutually approved, and then, they being of one and the same refined artistic taste, the style of decorations was found easy to decide upon.

Sullivan, perhaps, held some advantage as a judge of the requisite matériel. He knew to what extent he could rely upon finding actors and actresses who could at once be depended upon to speak the lines to the author's satisfaction, and, at the same time, be able to sing effectively and at least without actually murdering the music — in short, be capable of satisfying librettist and composer alike.

Gilbert, on the other hand, confessed to some lurking dread of

singers as actors — especially so of tenors; but then it was ever

his boast that he did not know a note of music, that he had not the

ear to distinguish "God save the King" from "Rule Britannia." On

this point, however, his Savoy associates were inclined to accept

this as half-truth, seasoned with a considerable amount of

Gilbertian sarcasm.

Gilbert, on the other hand, confessed to some lurking dread of

singers as actors — especially so of tenors; but then it was ever

his boast that he did not know a note of music, that he had not the

ear to distinguish "God save the King" from "Rule Britannia." On

this point, however, his Savoy associates were inclined to accept

this as half-truth, seasoned with a considerable amount of

Gilbertian sarcasm.

Anyway, our unmusical genius, the writer of lyrics that compelled melody, was often heard during rehearsals humming to himself some of the latest musical numbers. True, he generally jumbled ballads, bravuras, and patter songs into a strange potpourri wonderful to listen to, and in none of his renderings was he precise to Sullivan's original key; nevertheless, it was not always impossible to identify the tune or tunes intended, and certainly his efforts were good enough to raise speculation as to the limit of Gilbert's aural capacity.

This brief digression may, perhaps, help to throw some light on the question how our author and composer were guided in the selection of their company.

Piloted, then, by D'Oyly Carte, Gilbert and Sullivan exploited other lyric seas beyond that of the "legitimate" stage. At that time there existed none of those excellent, well organized, and drilled Amateur Operatic Societies that now prevail and which have become useful training-schools for the profession. But there was the Royal Academy of Music, from which "voices" were obtainable, and there was strolling about the kingdom a small army of quasi-theatrical entertainers who had won reputations in town-halls, mechanics' institutes, and other such places as might aptly and without disrespect be styled chapels-of-ease to the theatres. It was amongst the ranks of that army that The Three made search and eventually enlisted George Grossmith, Mrs. Howard Paul, and Rutland Barrington to fill principal parts in The Sorcerer.

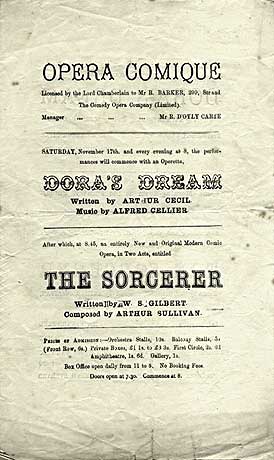

For leading baritone they appointed Mr. Richard Temple, who had proved his quality as an actor and singer in English opera of the Balfe school. For the tenor role they engaged Mr. Bentham, until then known only as a concert singer. The chorus was selected mainly from students of the Royal Academy and from other private sources. It was with more than ordinary interest and curiosity that play-goers anticipated the production of The Sorcerer, and accordingly, on the opening night, Saturday, November 17th, 1877, all musical London flocked to the Opèra Comique. Every one was on the qui vive of expectation, but none present on the occasion entertained the idea that they were witnessing the laying of the foundation-stone of an art institution that would in time become the delight of countless hearers and spectators.

The following is the original cast of —

| Sir Marmaduke Pointdextre (An Elderly Baronet) | Mr. Temple |

| Alexis (Of the Grenadier Guards — his Son) | Mr. Bentham |

| Dr. Daly (Vicar of Ploverleigh) | Mr. Barrington |

| Notary | Mr. Clifton |

| John Wellington Wells (Of J. W. Wells & Co., Family Sorcerers) | Mr. Grossmith |

| Lady Sangazure (A Lady of Ancient Lineage) | Mrs. Howard Paul |

| Aline (Her Daughter— betrothed to Alexis) | Miss Alice May |

| Mrs. Partlet (A Pew-opener) | Miss Everard |

| Constance (Her Daughter) | Miss Guilia Warwick |

Chorus of Villagers

Stage Manager — Mr. Charles Harris

Musical Director — Mr. G. B. Allen

The Scenery by Mr. Beverley.

The Dresses by Mdme Auguste.

The Dances by Mr. D'Auban.

The libretto of The Sorcerer was founded on a story which Gilbert had, a year previously, contributed to the Christmas number of The Graphic. The story set forth how a benevolently disposed and domestically happy clergyman, convinced that in marriage lies the secret of human bliss, administered a love-potion to his entire parish with the utmost indiscriminateness. The results did not turn out as anticipated. Everybody became enamoured of the wrong person, and the moral was that the principle of "natural selection," though it may not work with desirable activity, is the safest in the end.

The leading idea of the plot the — love-philtre business — was by no means novel. It had done service again and again in song, story, and play. It was, therefore, a severe tax on the ingenuity of our author to put new life into such old bones. But Gilbert proved equal to the task. His complete mastery of the art of giving to the most incongruous ideas the semblance of reason, his dialogue, rich in droll conceits and keen but playful satire upon men and things, his admirably turned lyrics brimming over with humour and often reaching to heights of pure poetry — in short, Gilbert's quaint original cut of new cloth succeeded in fitting an old garment perfectly to the taste of his clients.

Even if it were within the province of this book, it would be somewhat late in the day to enter into any critical analysis of The Sorcerer, either as regards the libretto or the music. Nevertheless, readers may like to learn something of what the press and public of the period thought of Gilbert and Sullivan's earlier works, and what promise they gave of things to follow.

A glance through the press notices shows that the only fault the critics could find with the book of The Sorcerer was that indicated above — the staleness of the joke attached to the love elixir, and the ultrasupernatural incidents which, perhaps, tended to make the play difficult of digestion.

Regarding the music let me quote one expert writer:

"Coming to Mr. Sullivan's music, we do not approach, as in opera generally, the be-all and end-all of the work. The ordinary libretto is scarcely more than a peg on which the composer hangs this theme, but here the importance of the playwright is at least as great as that of the musician, which in strictness should ever be the case. None the less do Mr. Sullivan's songs and concerted pieces command attention as the product of a cultivated, musical mind, and it is gratifying to state that The Sorcerer contains some of his best music. For the ballads we do not greatly care. They by no means come up to the composer's usual mark . . . but the musical charm of the opera lies in its concerted pieces— wherever, in point of fact, the composer had a dramatic incident or situation to illustrate."

Touching the acting and singing, the critics, without discovering "talent of the highest order anywhere on the stage," were yet generous enough in their praise to encourage the leading recruits of the new régime, and perfectly to justify the management in having placed their faith in new blood to give life to Gilbert and Sullivan's revolutionary creations.

The ultimate success of The Sorcerer may be judged by the fact that its run extended from November 17th, 1877, to May 22nd, 1878, comprising 175 performances — no slight achievement in those days.

The Sorcerer, on its first production, was preceded by a one-act operetta, Dora's Dream, written by Arthur Cecil and composed by Alfred Cellier. The characters were played by Miss Giulia Warwick and Mr. Richard Temple. This little piece was, on February 9th, 1878, superseded by The Spectre Knight, a one-act opera, the libretto by James Albery and the music again by my brother Alfred, who had then succeeded Mr. G. B. Allen as Musical Director of the Opèra Comique.

I trust I may be forgiven if, in parenthesis, I here note with pride that the overture to The Spectre Knight remains a living work, and, if I may be allowed to add, has proved worthy of the composer of the cantata Gray's Elegy, and the operas Dorothy, Doris, The Mountebanks, etc.

|

Page Updated 4 August, 2011